Working until retirement increasingly common in Finland – unemployment just before retirement halved among the low-educated

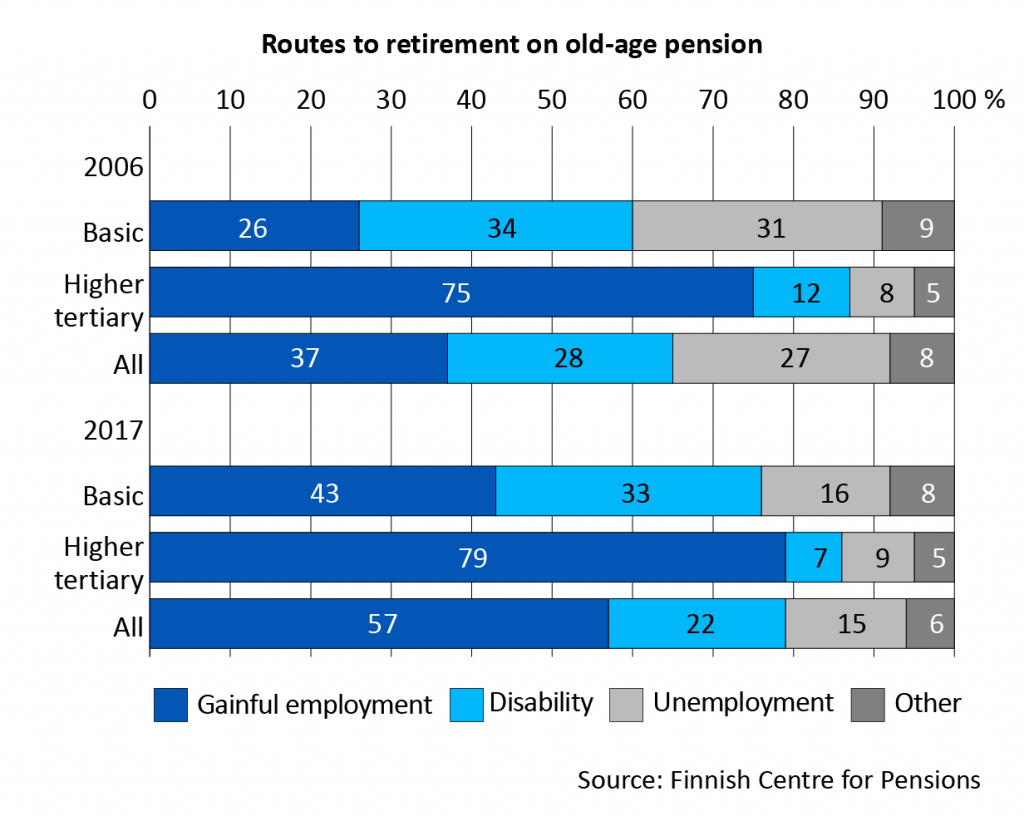

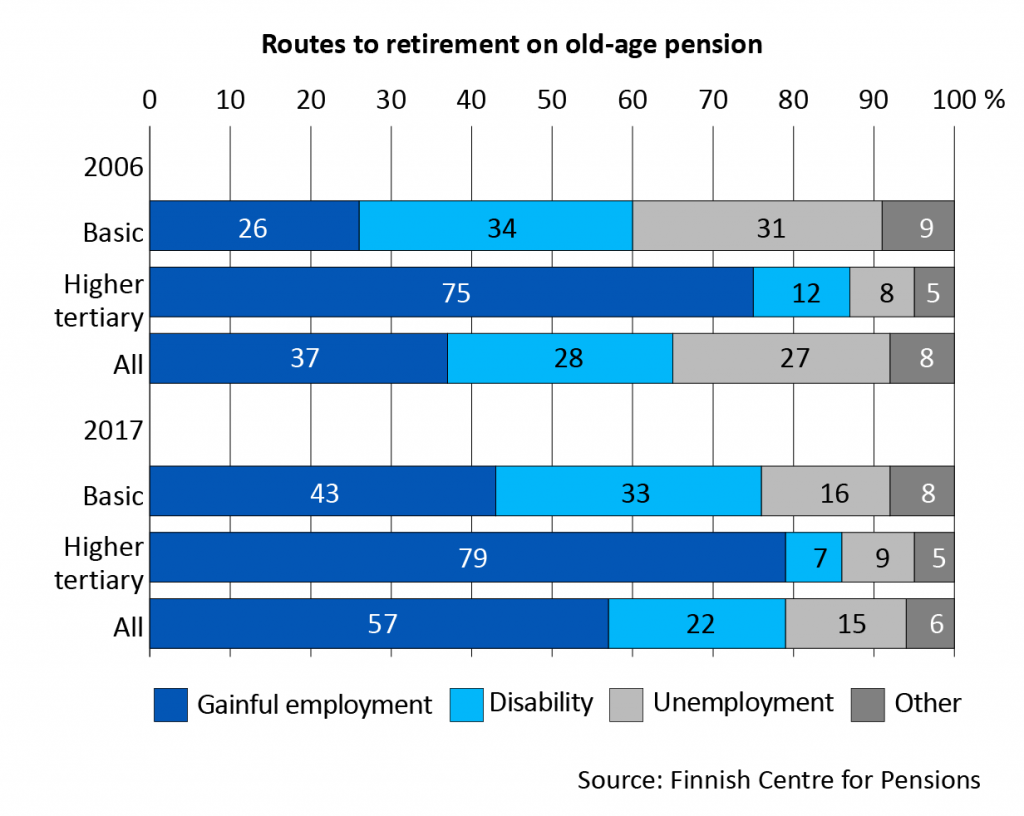

Finns continue working until retirement on an old-age pension clearly more often than before. Retirement from work became more prevalent in all socio-economic groups in 2006–2017, but particularly so among the low-educated. This is evident from a fresh study by the Finnish Centre for Pensions.

In 2017, nearly 60 per cent retired on an old-age pension from work. In 2006, the equivalent proportion was slightly under 40 per cent. Slightly less than half of the low-educated and blue-collar workers retired from work in 2017, while an ample decade earlier, nearly three out of four exited working life before reaching their retirement age.

In fact, according to Economist Satu Nivalainen (Finnish Centre for Pensions), unemployment just before retirement has nearly halved among the low-educated during the review period.

Nivalainen assesses that the trend is based on the abolishment of the unemployment pension agreed on in connection with the 2005 pension reform and the rising age limits of the unemployment tunnel.

“It is surprising that the changes made to the unemployment tunnel has so significantly increased working until retirement among the low-educated. At the same time, the socio-economic gaps in unemployment have levelled out since unemployment before retirement has not declined among the high-educated,” Nivalainen explains.

Working lives extended towards the end of the review period in the public but not in the private sector

In the public sector, the working lives of wage-earners who worked until retirement have been shorter than in the private sector in 2006–2017. However, working lives have extended more in the public than in the private sector. In the public sector, working lives in the age range 53-68 have increased.

According to Nivalainen, retirement has been deferred especially in the public sector. Late retirement is linked to the fact that, among new retirees in the public sector, increasingly few have an occupational retirement age that is under 63 years of age while higher individual retirement ages have become more common.

“In the private sector, however, retirement has not been deferred and, in practice, working lives have not extended at all towards the end of working life since 2006”, Nivalainen says.

In connection with the 2005 pension reform, the retirement age became flexible (63–68-years). The accelerated accrual rate that was applied after age 63 was hoped to entice people to work late.

“If the accelerated accrual rate had worked as planned, the effect should have been visible especially in the private sector.”

Particularly the high-educated benefited from accelerated accrual rate

The socio-economic differences in length of working life narrowed in 2006–2017 as the low-educated and blue-collar workers increasingly often worked until old-age retirement.

Nevertheless, the low-educated have continued working past their retirement age less often than before. Instead, the high-educated and those in a good position in working life have clearly deferred retirement.

“The high-educated and those well-off in society in particular have taken advantage of the accelerated accrual rate that applied for work done after reaching one’s retirement age. This may have contributed to socio-economic differences in pension levels.” The study examines socio-economic differences in the transition to old-age pension and working lives after the 2005 pension reform but before the 2017 pension reform took effect.

Read the research publication’s summary in English: Socio-economic differences: retirement and working lives in 2006, 2011 and 2017