Impacts of 2017 and 2005 pension reforms

The most recent extensive pension reform came into force in 2017. The previous major pension reform was in 2005. The studies have assessed how the reforms have affected the length of working lives and the timing of retirement.

Pension reform 2017

Following the 2017 pension reform, the retirement age increased, pension accrual rates were adjusted and two new pension benefits were introduced: the partial old-age pension and the years-of-service pension.

The aim of the 2017 reform was to encourage people to work longer, to ensure sustainable pension financing and to consider the sustainability gap in public finances. Since the reform, the employment rate of 63-year-olds has increased, and people retire at a later age than before. The partial old-age pension has become a popular benefit.

Rising retirement age

-

- The retirement age rises by three months per age group as of the 1955 birth cohort. For those born between 1962 and 1964, the retirement age is 65 years. For persons born in 1965 and later, the threshold for old-age pension will be tied to life expectancy.

- The reform introduced the target retirement age, which is higher than the retirement age. The target retirement age is the age at which the pension-reducing effect of the life expectancy coefficient has been offset by the increment for late retirement.

Pension accrual and the increment for late retirement

- Pension accrues at a rate of 1.5 per cent of the annual earnings as of age 17 until the age at which the insurance obligation ends.

- During the transition period in force until the end of 2025, 53–62-year-olds accrue pension at a rate of 1,7 per cent of their annual earnings.

- Retiring late is rewarded by an increment which increases the accrued pension by 0.4 per cent for each month that retirement is deferred past the retirement age.

New pension benefits

- Partial old-age pension: A person can take 25 or 50 per cent of their accrued old-age pension at age 61 at the earliest. For those born in 1964, the age limit is 62 years. When drawing a partial old-age pension early, the part taken is permanently reduced by 0.4 per cent for each month that the pension is taken early (before reaching the retirement age).

- Years-of-service pension: The years-of-service pension can be granted to a person who has turned 63 years and who has done hazardous or arduous work for a long time and whose ability to work has been reduced.

Key pension rules in 2005–2016 and since 2017

| Pension rule | 2005–2016 | Since 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Retirement age (old-age pension) | Flexible retirement age. Retirement age 63 years. Insurance obligation ends at age 68. | Flexible retirement age. The retirement age rises by 3 months per birth cohort as of those born in 1955 until it is 65 years (for those born in 1962–1964), after which the retirement age is linked to the growth in life expectancy. The age at which the insurance obligation ends rises to 70 years. |

| Pension accrual rates at different ages | 18–52-year-olds: 1.5% of annual earnings 53–62-year-olds: 1.9% of annual earnings |

From age 17 until the age at which the insurance obligation ends: 1.5% of annual earnings. Between 2017–2025, pension accrues at a rate of 1.7% for the 53–62-year-olds. |

| Pension accrual after reaching the retirement age | Accelerated accrual rate of 4.5% for the 63–68-year-olds. Increment for deferred retirement 4.8% per year after age 68. | Accrual rate 1.5% of annual earnings. Increment for deferred retirement 4.8% per year after reaching the retirement age. |

| Part-time pension | Age limit 61 years as of 2015. Required transfer from full-time to part-time work. No deduction was made to the old-age pension. | – |

| Partial old-age pension | – | As of age 61. For those born in 1964, the age limit is 62 years, after which the limit rises in line with the rising retirement age. It is possible to take 25% or 50% of the accrued earnings-related old-age pension. |

| Reduction for early retirement | – | In partial old-age pension: 4.8% per year when drawn before reaching the retirement age. |

| Years-of-service pension | – | Requires 63-years-of age and at least 38 years of hazardous and arduous work. One’s ability to work must be reduced. |

| Pension-reducing life expectancy coefficient | Yes | Yes |

Read more on Etk.fi:

Key results

- Employment rates have clearly improved following the 2017 pension reform.

- The employment rate has increased 1.7-fold because of a three-month increase per year between the former and the new retirement age.

- Unemployment, disability and being outside the labour force has also increased between the former and the new retirement age.

- The effective retirement age of those who have continued in employment until their retirement age has increased clearly and working lives have been extended by several months.

Rising retirement age has clearly improved the employment rate

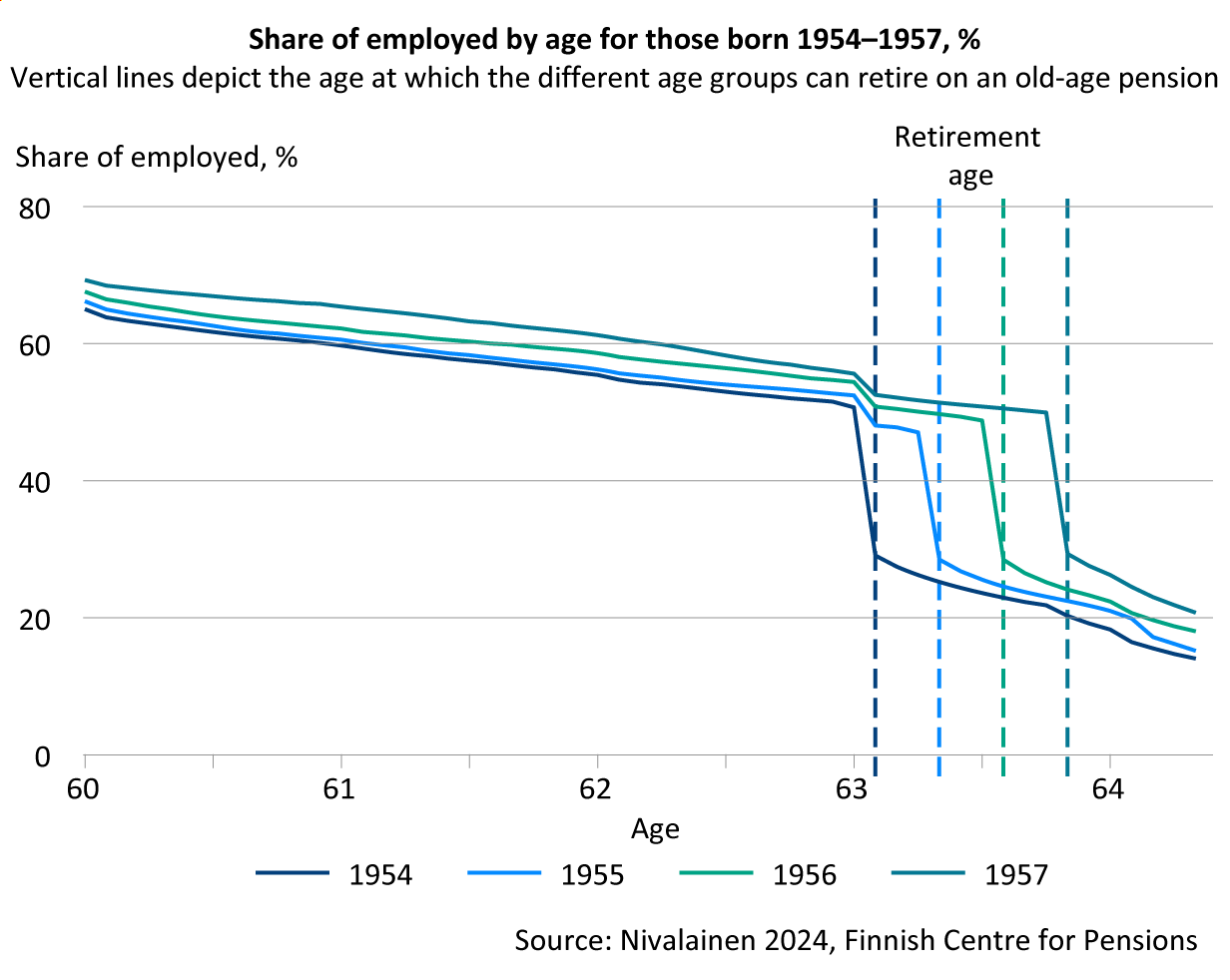

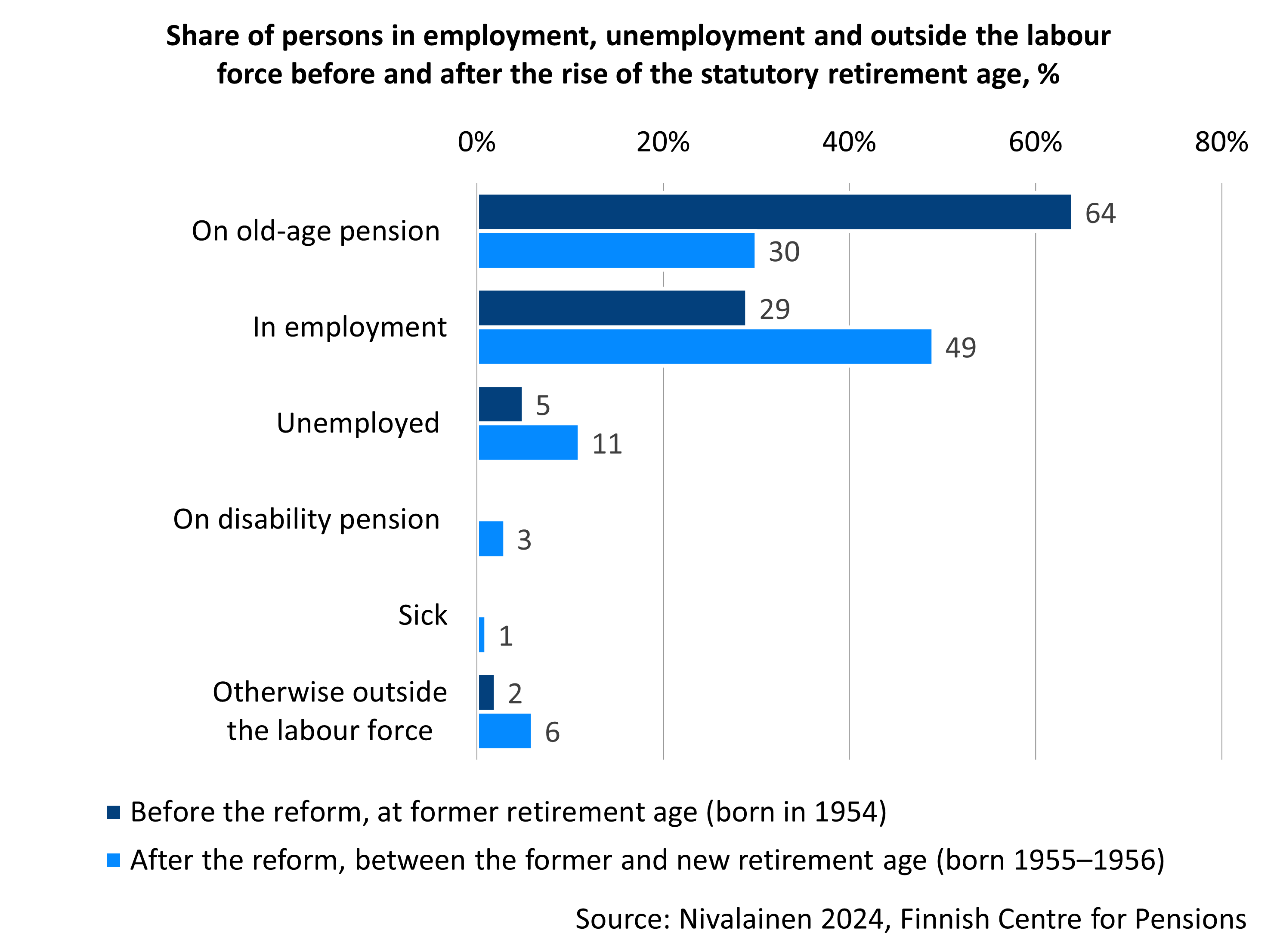

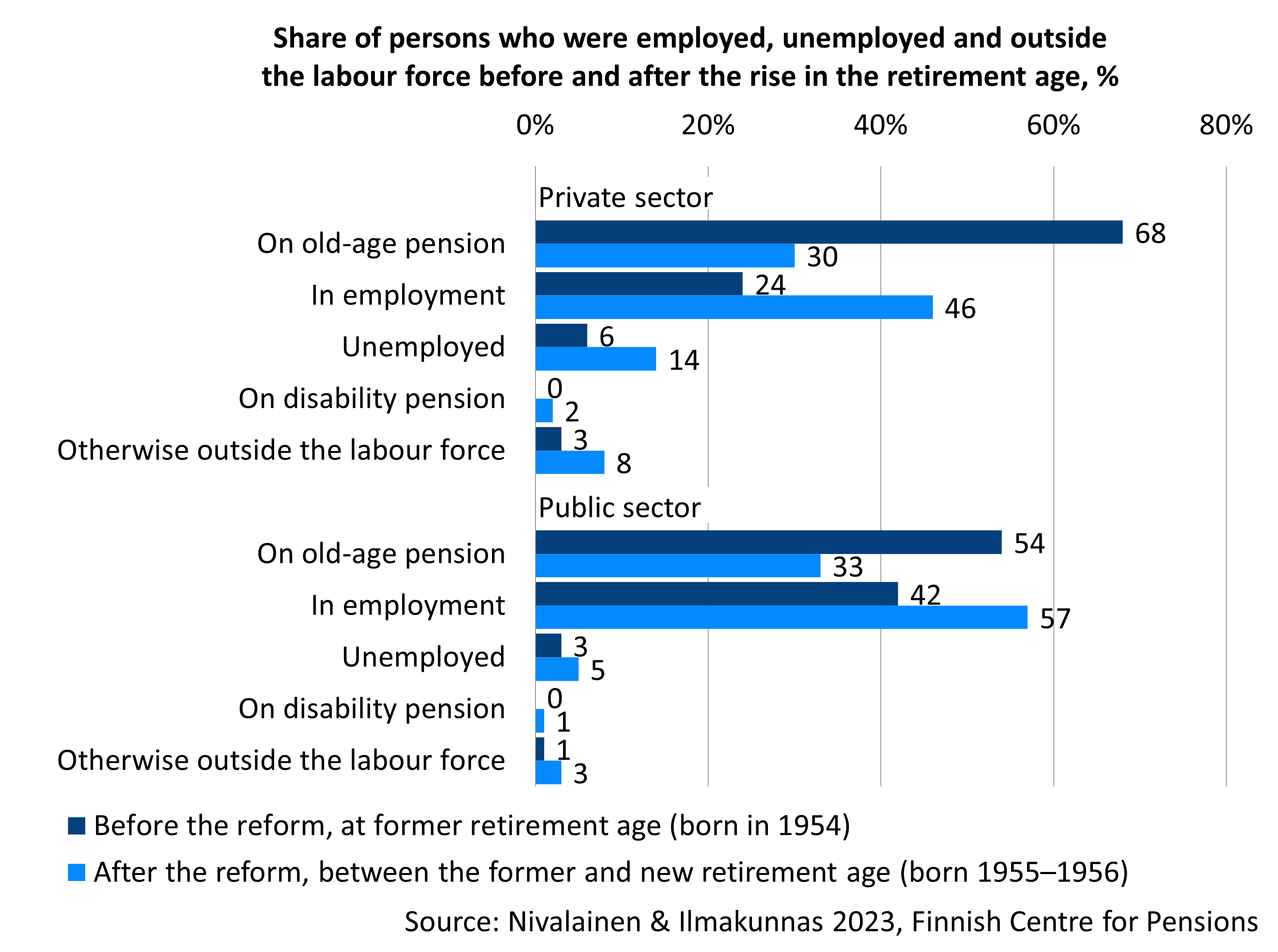

The rising retirement age has improved the employment rate. The employment rate has increased 1.7-fold between the former and the new retirement age because of the rising retirement age. Those born between 1955 and 1957 were the first age cohorts whose retirement ages rose. After the reform, around 50 per cent of them were in employment after they had turned 63 years. Before the reform, the corresponding share among those born in 1954 was 29 per cent.

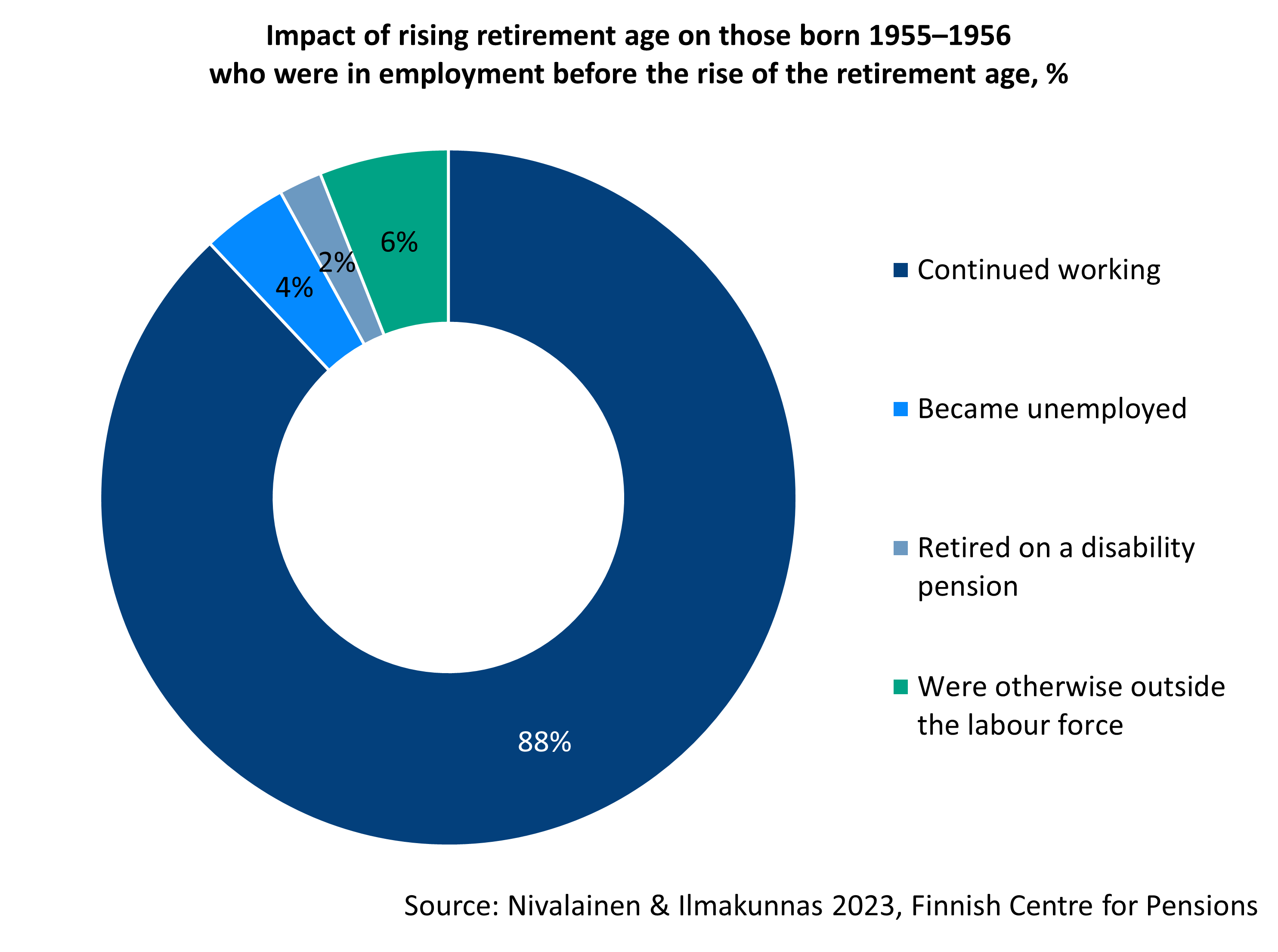

The rising employment rate explains around 60 per cent of the reduction in retirement between the former and the new retirement age. Of those who had been forced to defer retirement due to the rising retirement age, 62 per cent were in employment after the reform. Most of the increased employment rate can be explained by the fact that those of working age have remained in employment longer due to the rising retirement age.

Due to the reform, the share of those unemployed, on a disability pension or otherwise outside the labour force has also increased clearly. Nearly 40 per cent of those who would already have been on an old-age pension were it not for the rising retirement age were outside the labour force as a result of the pension reform. For the most part, this is because the rising retirement age extends unemployment or the time spent on a disability pension.

Although most of the employed have extended their working lives due to the rising retirement age, some have exited working life. A total of 12 per cent of those who were in employment but who would have retired already were it not for the rising retirement age, had become unemployed, had retired on a disability pension or were otherwise outside the labour force.

A three-month increase in the retirement age has extended the working life of those born in 1955 by 0.6 months, while a six-month increase in the retirement age has extended the working life of those born in 1956 by 1.3 months.

Overall, fiscal savings in retirement benefit payments due to postponed retirement and additional tax revenues from increased employment are

partly offset by the rising costs of other social security programs. The total net fiscal gain from a one-month increase in the retirement age has been around 34 million euros per cohort.

Publications:

- Nivalainen & Ilmakunnas 2025. Increasing Statutory Retirement Age, Labor Market Outcomes and Effect Heterogeneity: The 2017 Pension Reform in Finland (Julkari)

- Nivalainen 2024. Vanhuuseläkeiän nousun vaikutukset vuosina 1954-1957 syntyneillä ja sosioekonomiset erot. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen & Ilmakunnas 2023. Pension reform 2017: Impact of rising old-age pension age on employment and other labour market states (Julkari)

Impact of rising retirement age differs by employment sector and educational level

After the 2017 pension reform, the share of working over-63-year-olds has increased more in the private than in the public sector. The employment rate has nearly doubled between the former and the new retirement age in the private sector, and in the public sector, it has grown 1.4-fold.

The growth is slower in the public sector because it was more common even before the 2017 pension reform to work past the retirement age than in the private sector.

In the private sector, the share of persons who are unemployed, on a disability pension and otherwise outside the labour force has grown more than in the public sector. In the private sector, the employment growth explains less than 60 per cent of the reduction in retirement between the former and the new retirement age. In the public sector, the equivalent share is 70 per cent. In the private sector, more of the impact of the rise in the retirement age is diverted away from work.

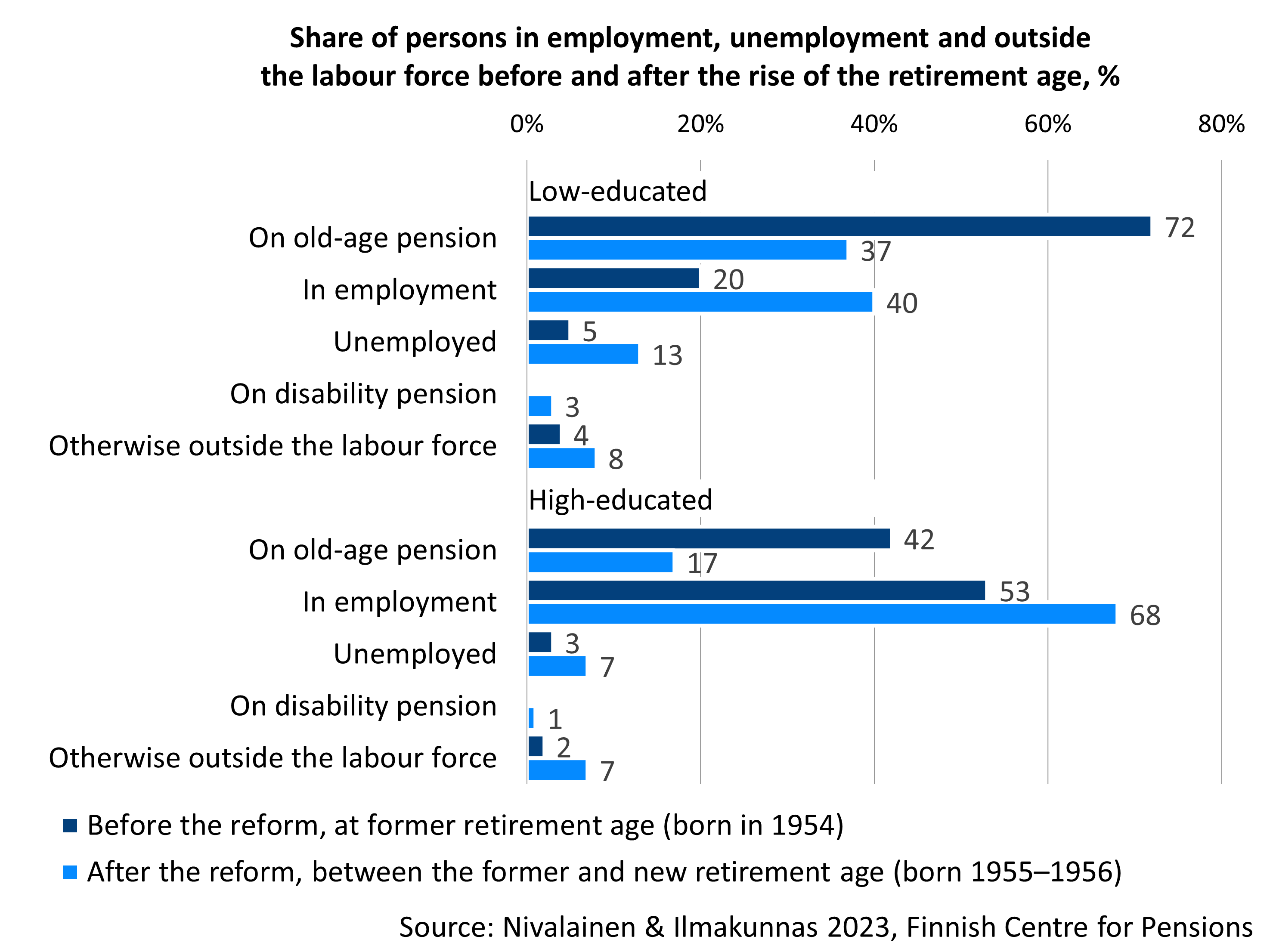

Among the low-educated, the share of persons employed, unemployed, on a disability pension or otherwise outside the labour force has grown more than among the high-educated. This difference is explained by the fact that a clearly higher share of the high-educated continued working past the retirement age already before the 2017 pension reform. Pre-retirement unemployment and disability is also lesser among the high-educated than the low-educated.

The employment growth among the low-educated explains less than 60 per cent of the reduction in retirement between the former and the new retirement age. Among the high-educated, the equivalent share is over 60 per cent.

Because of the 2017 pension reform, employment among men has risen slightly more than among women. For both men and women, the employment growth explains about half of the reduction in retirement between the former and the new retirement age.

Publications:

Deferred retirement on an old-age pension from employment

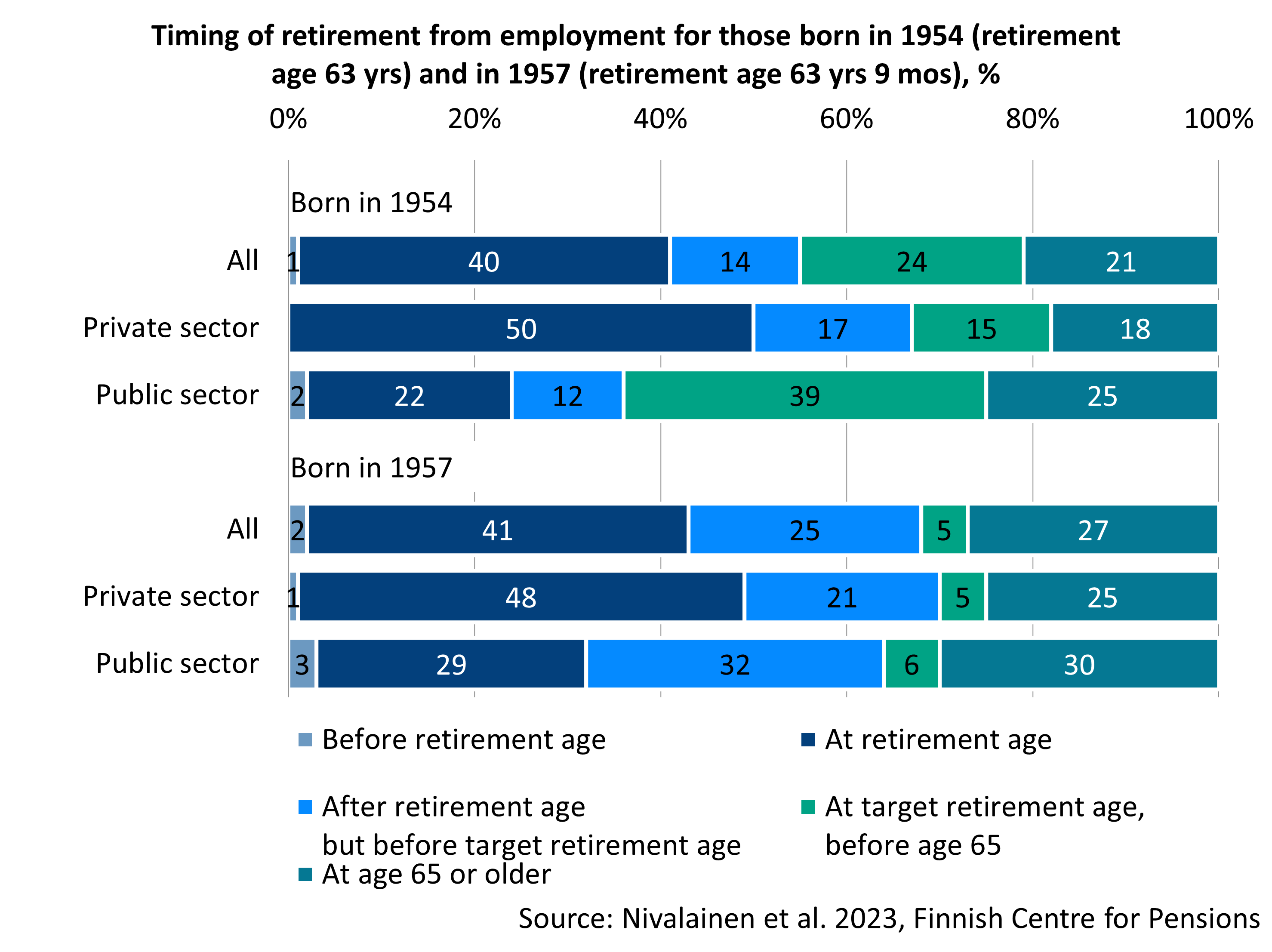

After the 2017 reform, retirement at the retirement age has not increased among those in employment even though the retirement age has risen.

The retirement age of those born in 1954 was 63 years, and 40 per cent retired when they reached that age. The retirement age of those born in 1957 was 63 years and 9 months and, again, 40 per cent retired when they reached that age.

The share of persons retiring at their retirement age has remained on the same level in the private sector. In the public sector, the share has grown slightly. Yet it is clearly less common for workers in the public sector to retire as soon as they reach their retirement age.

For those born in 1954, the retirement age is 63 years and 9 months, and for those born in 1957, it is 64 years and 9 months. As the target retirement age rises, the share of persons in employment until then has declined. At the same time, the gap in the share of those in employment until this age in the private and the public sector has narrowed.

The share of public sector workers born in 1954 who were in employment until at least their target retirement age was nearly twice as high compared to the private sector. The gap between the sectors was merely a few percentage points for those born in 1957.

The share of persons in employment until age 65 at least has grown in both sectors. It is slightly more common to work until this age in the public sector than in the private sector.

Retirement on an old-age pension deferred clearly

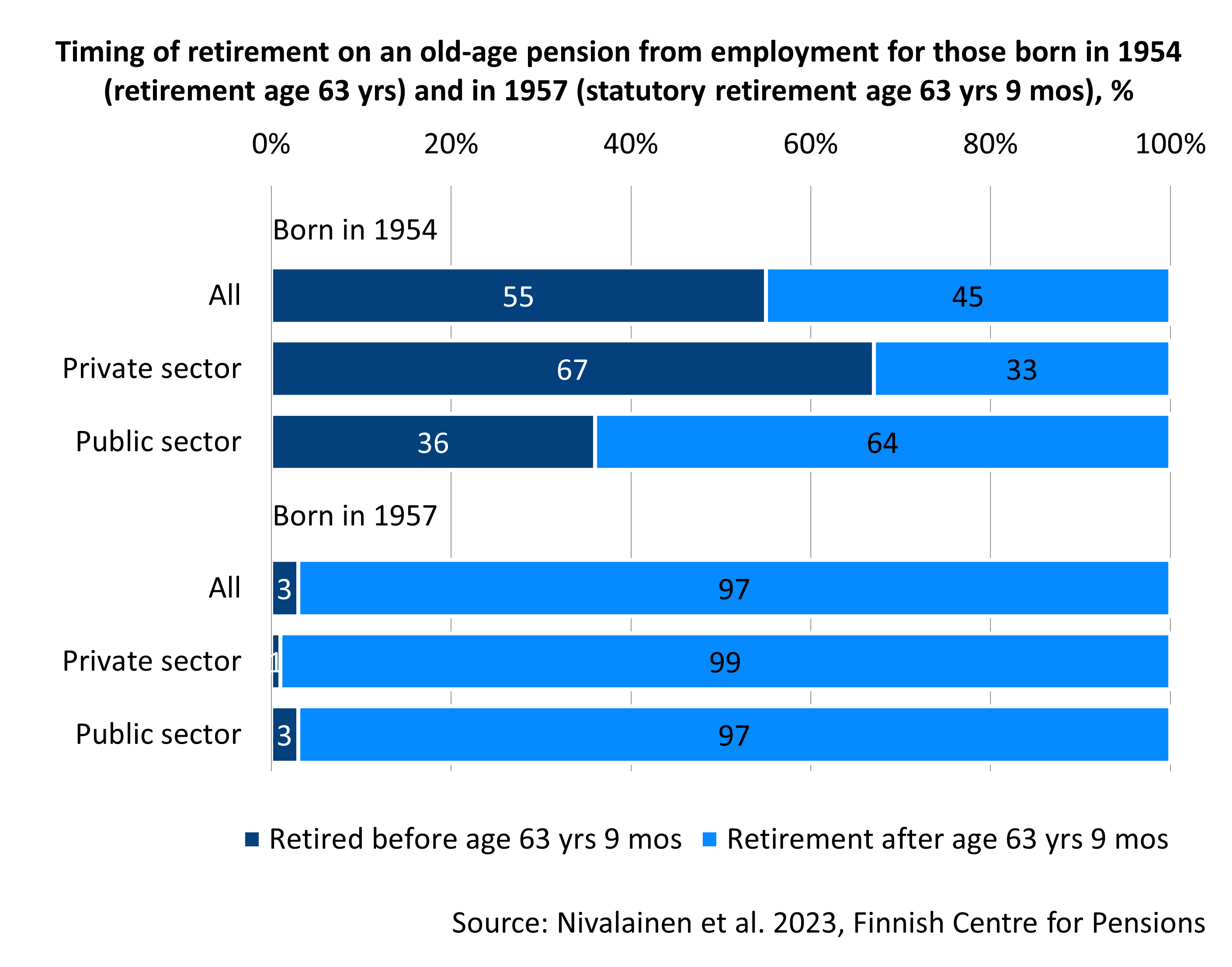

As a result of the 2017 pension reform, retirement among those who worked until they retired has been deferred clearly.

Of those born in 1954, whose retirement age was 63 years, more than half retired on an old-age pension from employment before the age of 63 years and 9 months. The retirement age of those born in 1957 was 63 years and 9 months so, in practice, they all retired on an old-age pension after that age.

In the private sector, retirement has been clearly more deferred than in the public sector.

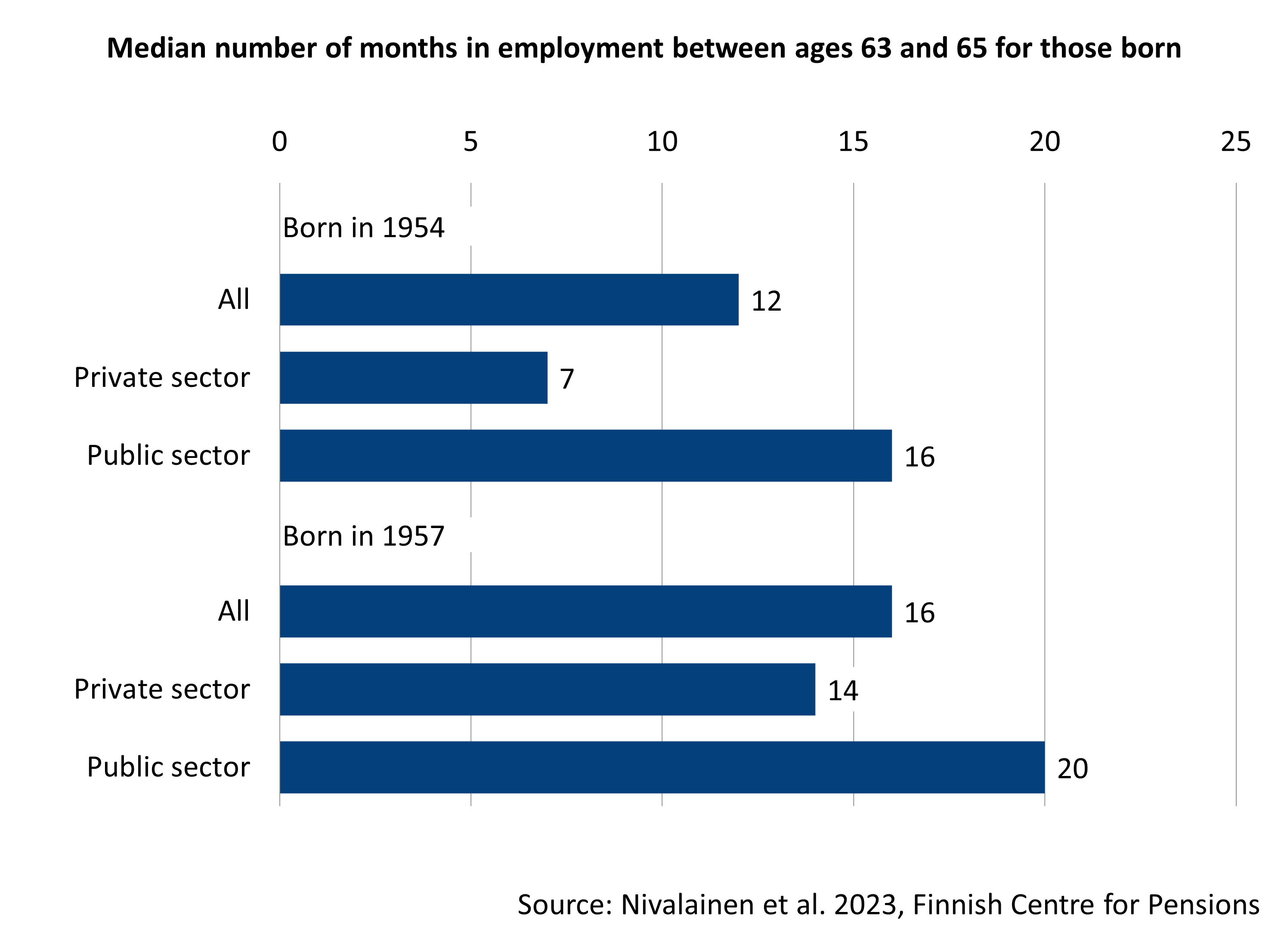

Extended working lives at career-end

As a result of the rising retirement age, working lives have extended among those who work until their retirement age. Between the ages of 63 and 65 years, those born in 1957 worked for four months longer than those born in 1954. That means that the rise in the retirement age has not transferred in full to the number of months working.

In the private sector, the number of months working has grown considerably more than in the private sector in this age interval. Yet, in the public sector, persons are working longer after age 63 than in the private sector.

Publications:

Key results

- Nearly half of those approaching their retirement age assess that they will retire at that age.

- The intended retirement age has risen at the same pace as the retirement age for the old-age pension.

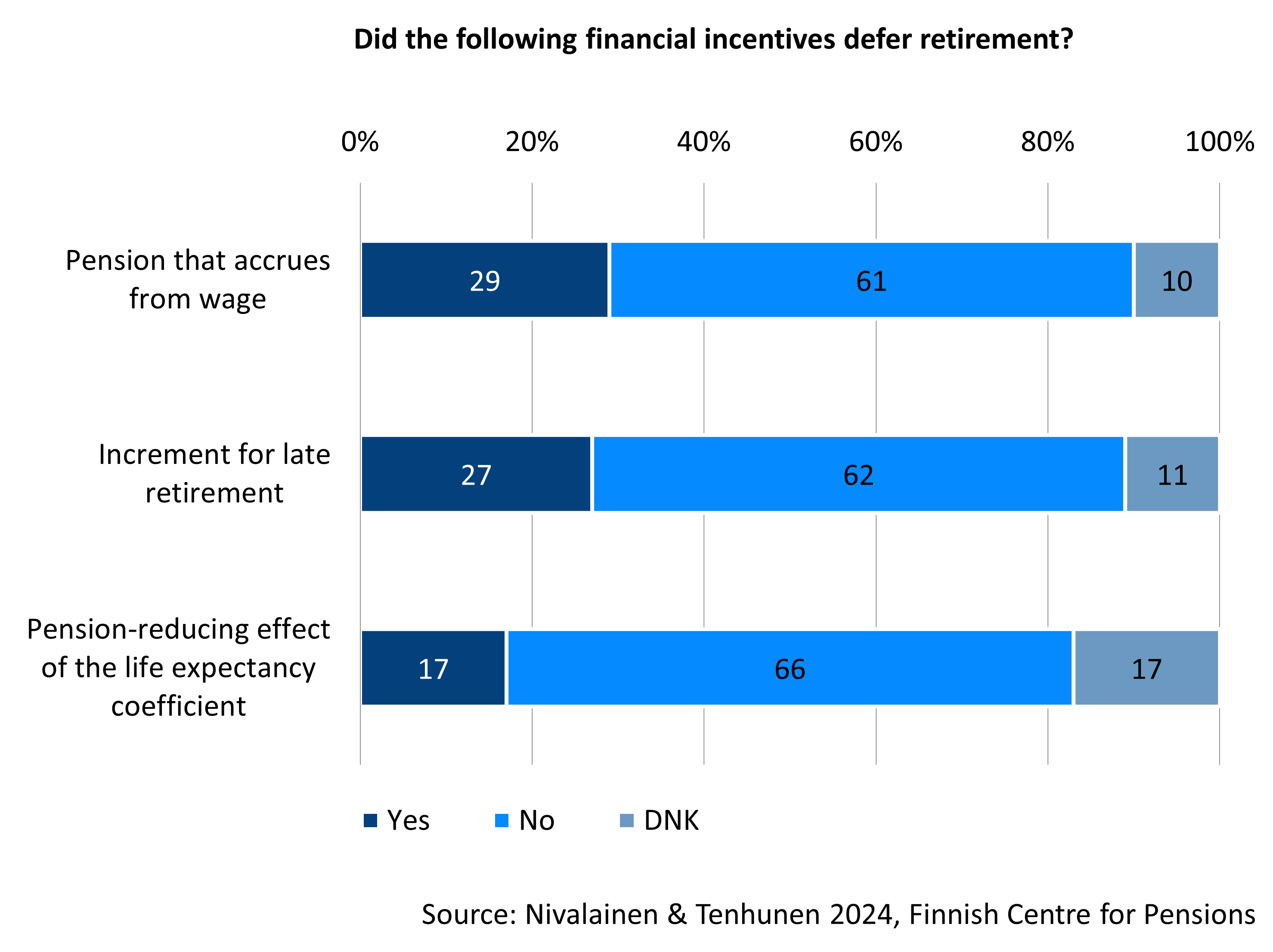

- Every sixth person approaching their retirement age and more than every fourth newly retired on an old-age pension assesses that financial incentives have affected the timing of their retirement.

- Those retiring from employment felt that the increment for late retirement and the pension that accrues from the wage they receive encourage them to defer retirement more often than the pension-reducing effect of the life expectancy coefficient.

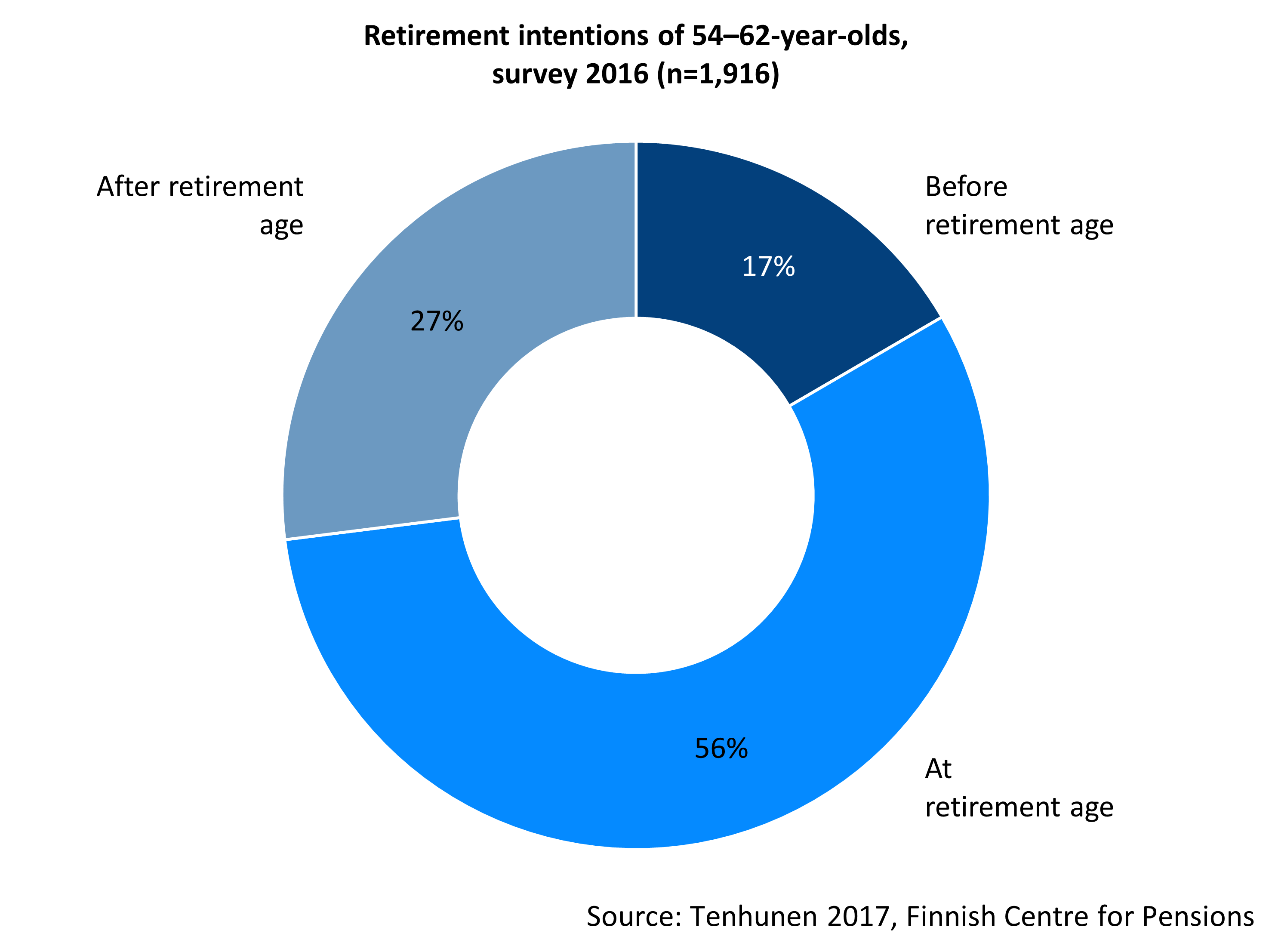

Most intend to retire at their retirement age

Although the retirement age rises following the 2017 pension reform, most defer their retirement intentions in line with the rising retirement age. According to a survey carried out in 2016, before the pension reform, more than half of those Finns approaching their retirement age assessed that they would retire at the retirement age of their age cohort. One in six estimated to retire early, while just over a quarter estimated to retire late.

Those closer to their retirement age assessed more often than average that they would retire after reaching their retirement age. There were no differences between men’s and women’s retirement intentions. Self-employed person and persons working in the public sector, on the other hand, considered early and late retirement more often than others.

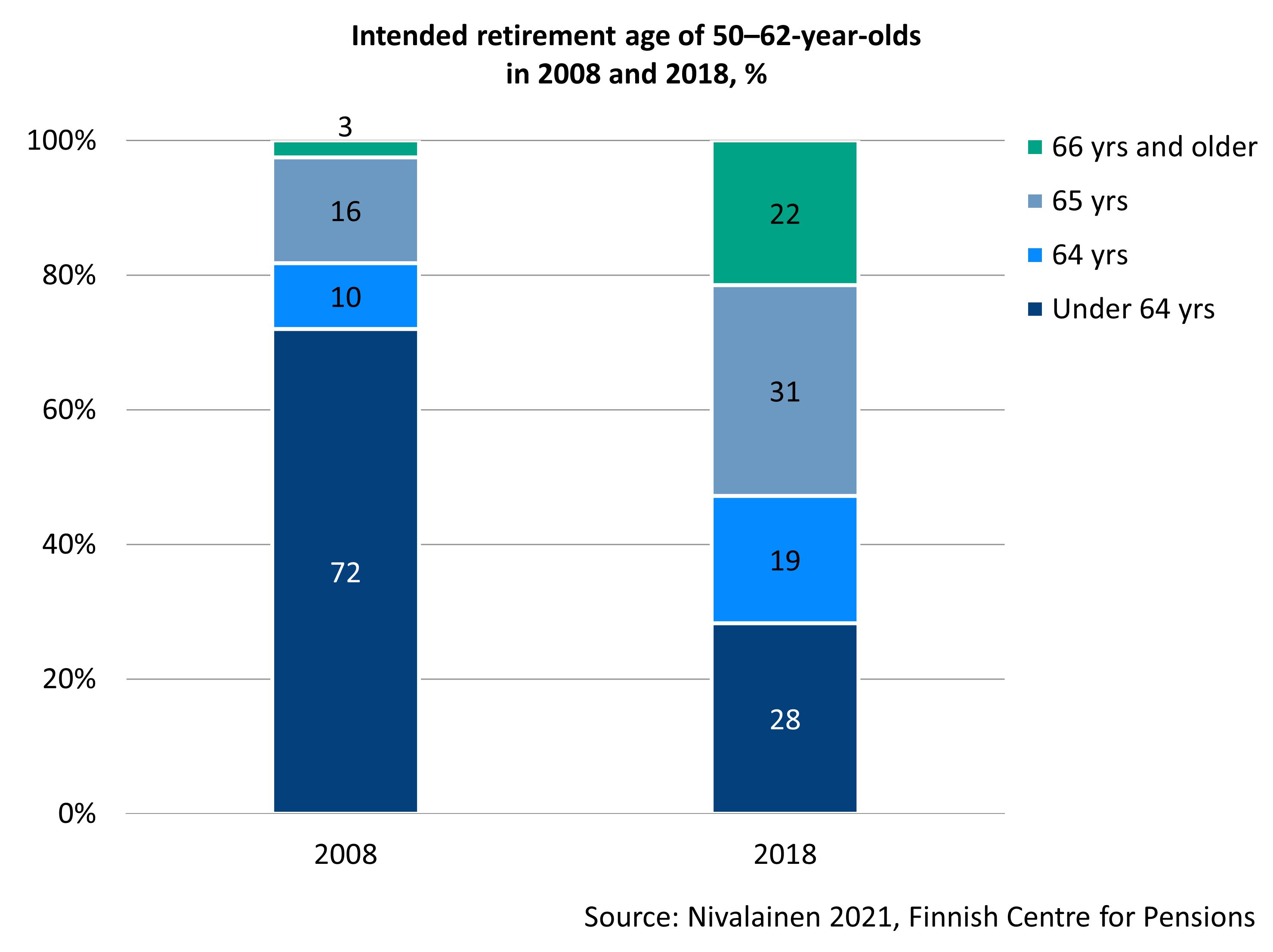

Retirement intensions deferred – intended retirement age follows the retirement age for the old-age pension

Based on data from Statistics Finland’s 2008 and 2018 Quality of Life Surveys, the intended retirement age of wage earners who have turned 50 follows the retirement age of the old-age pension. The intended retirement age has risen at the same pace as the retirement age for the old-age pension. For example, an increase of one year in the retirement age has raised the intended retirement age by one year.

The average intended retirement age has increased between 2008 and 2018 by nearly two years, from 62.7 years to 64.6 years. In 2018, every second person intended to retire at the earliest at age 65 or older. In 2008, this was the intention of only every fifth person.

The retirement intentions of wage earners have been observed to successfully predict the effective retirement age.

Own old-age retirement age strongly determines the intended retirement age

In 2018, slightly less than half of the 50-year-old or older wage earners intended to retire at their retirement age. One fourth intended to retire early, before their retirement age, and nearly every third intended to retire late, after their retirement age.

Men, the high-educated, upper-level employees, those who perceived their ability to work to be good, those who lacked a spouse and those for whom work was a very important area in life intended to retire late.

Persons working in the private sector and those with a weaker ability to work or long sickness absences planned more often to retire earlier than usual.

Those who intend to retire late

- Men

- Highly educated

- Upper white-collar employees

- Those with a perceived good ability to work

- Those lacking a spouse

Publications:

- Nivalainen 2021. Changes in retirement intentions in 2008–2018 and retirement intentions in 2018 (Julkari)

- Nivalainen 2022. From plans to action? Retirement thoughts, intentions and actual retirement: an eight-year follow-up in Finland (Aging and Society)

- Nivalainen 2023. Retirement Intentions and Increase in Statutory Retirement Age: 2017 Pension Reform and Intended Retirement Age in Finland (Journal of Aging & Social Policy)

- Tenhunen 2017. Flexible retirement age at a later age – Survey on the 2017 pension reform and the intentions to continue working (Julkari)

Financial incentives reflected in retirement intentions and experiences of those who have retired

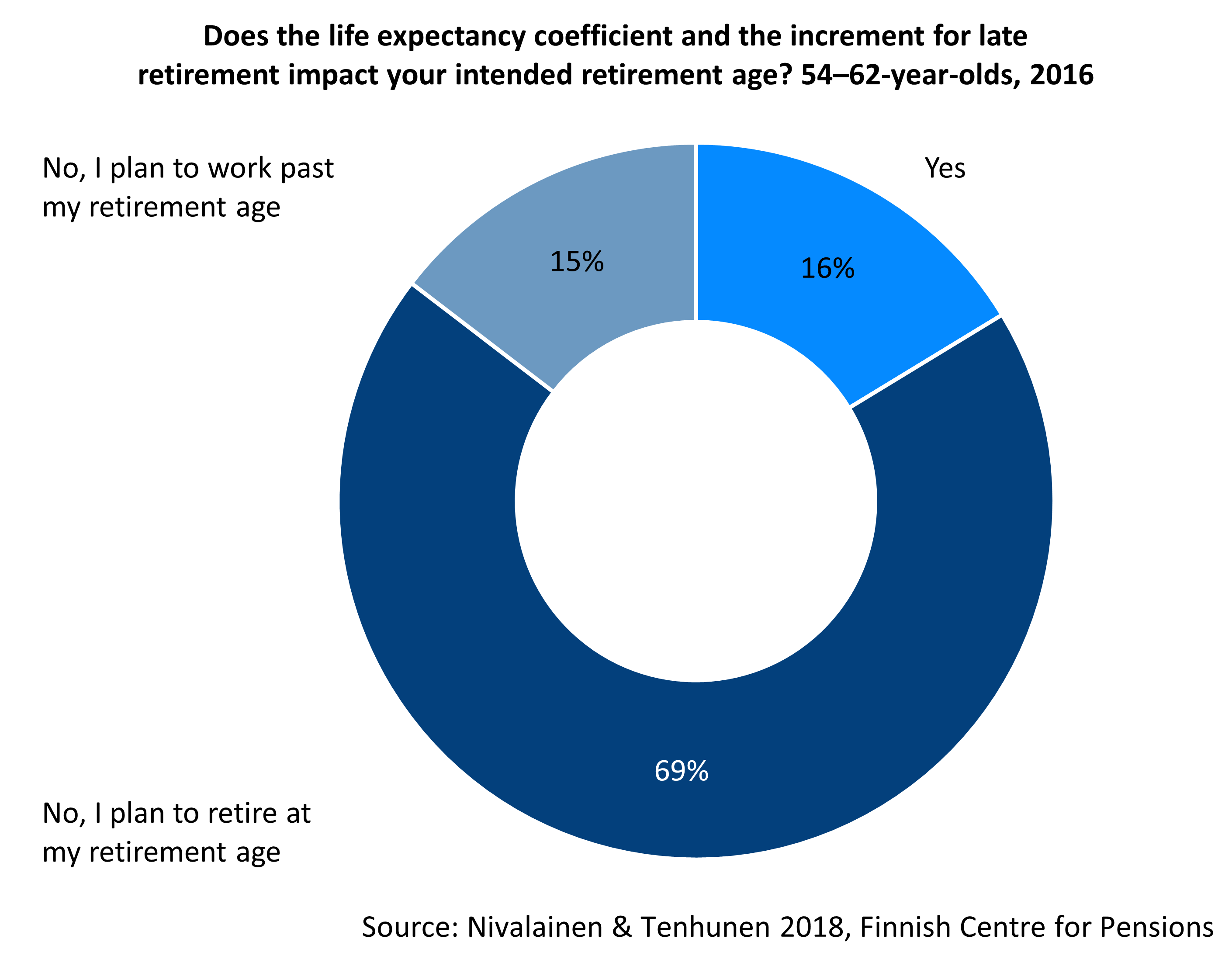

The pension-reducing impact of the life expectancy coefficient and the increment for late retirement are financial factors which are hoped to encourage extended working.

In a survey conducted in 2016, half of the 52–64-year-old Finns thought that, on a general level, the increment for late retirement encourages late retirement. Yet only around 16 per cent of those approaching their retirement age perceived that the life expectancy coefficient and the increment for late retirement encourage them to continue working past their retirement age. Nearly as many assessed that they would continue working past their retirement age, regardless of the financial incentives.

Those who felt that the life expectancy coefficient and the increment for deferred retirement impacted their retirement plans intended more often than others to retire after reaching their own retirement age. The same applied to those who felt the increment for late retirement to be encouraging on a general level.

Of those who retired on an old-age pension from employment in the years 2019–2021, slightly less than 30 per cent felt that the increment for late retirement and the pension that accrues from their wage encouraged them to defer retirement.

The pension-reducing effect of the life expectancy coefficient was perceived as an incentive by 17 per cent of the respondents. There was also more uncertainty about the incentiveness of the life expectancy coefficient than the other financial incentives.

Men, those who retired late and the high-educated perceived more often than others that the financial incentives encouraged late retirement.

Publications:

- Nivalainen & Tenhunen 2018. Pension knowledge, impact of economic incentives and retirement intentions (Julkari)

- Nivalainen & Tenhunen 2024. Financial incentives or working conditions – Which prompt to extended working? Survey for persons who retired on an old-age pension from gainful employment in 2019–2021. (Julkari)

Key results

- More than every third takes out the partial old-age pension early, before reaching their retirement age. The partial old-age pension has been clearly more popular than its predecessor, the part-time pension

- Most take the partial old-age pension at age 61.

- Around 80 per cent of all persons who have taken the partial old-age pension have taken 50 per cent of their accrued pension.

- Men, self-employed persons, private sector workers, unemployed persons or those with a longer working life are more likely than others to take the partial old-age pension before retiring on a full old-age pension.

The partial old-age pension has been clearly more popular than its predecessor, the part-time pension

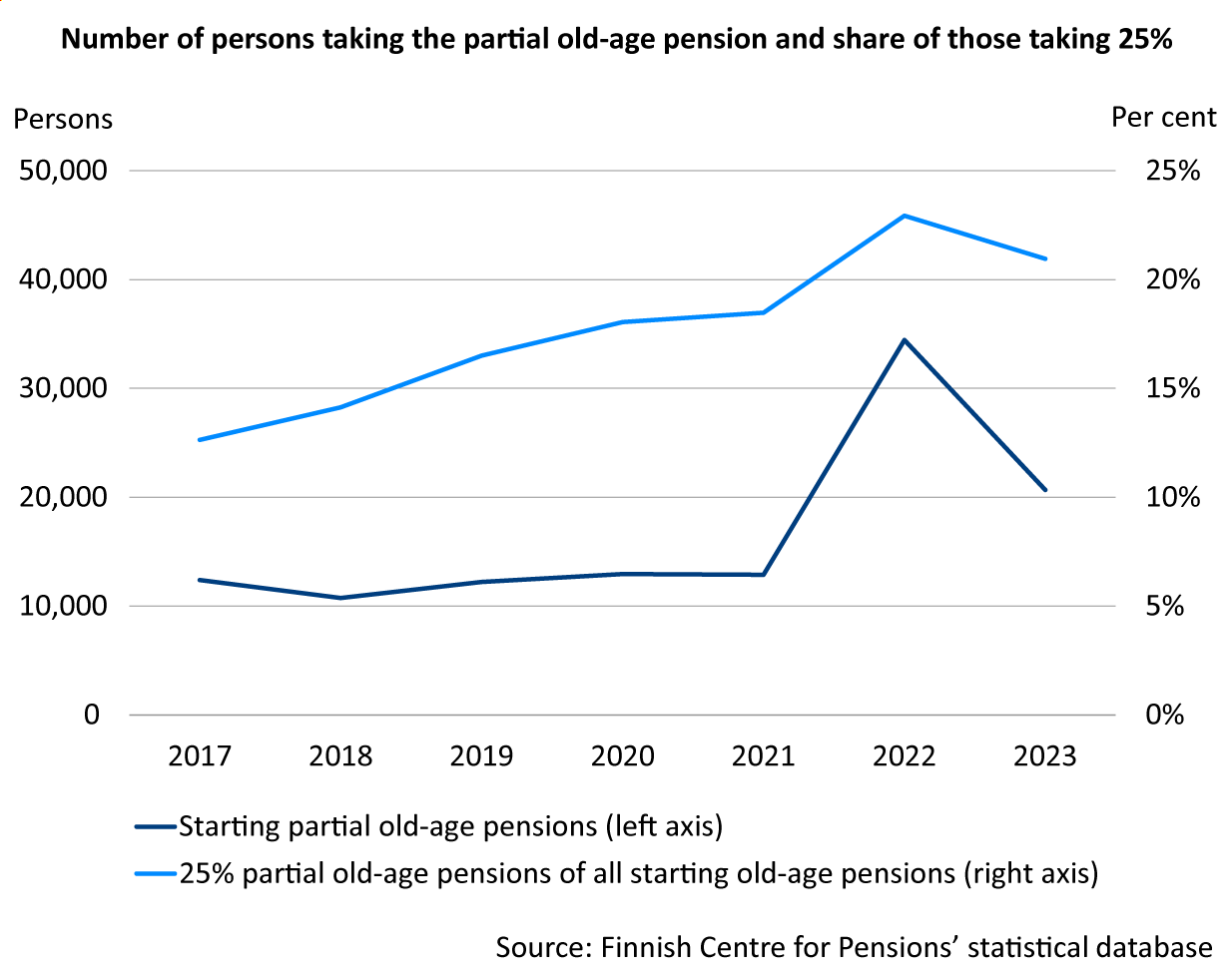

Since the eligibility age for the part-time pension changed to 61 years, the number of persons taking out this pension decreased to less than 5,000 persons per year. After the 2017 pension reform, around 12,000–13,000 persons have taken the partial old-age pension each year. In 2022, however, a clearly larger number of persons than before took the partial old-age pension due to the exceptional earnings-related pension index of 2023.

Around 80 per cent of all persons who have taken the partial old-age pension take 50 per cent of their accrued pension. Nevertheless, the share of persons taking 25 per cent of their accrued pension has grown.

Read more on Etk.fi:

Publications:

- Kannisto 2023. Osittainen varhennettu vanhuuseläke ja työuraeläke. Uudet eläkelajit 2022. [Partial old-age pension and the years-of-service pension: new pension benefits in 2022]. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen et al. 2021. Partial old-age pension. A picture of claimants in 2017–2020 (Julkari)

- Nivalainen & Tenhunen 2025a. Osittaisen vanhuuseläkkeen varhennettuna ottaneiden ominaisuudet vuosina 2020-2023 [Characteristics of partial old-age pension claimants 2020-2023] (Julkari)

Partial old-age pension usually taken close to the lower age limit

Gender, labour market status, employment sector and length of working life are linked to the probability of pension uptake.

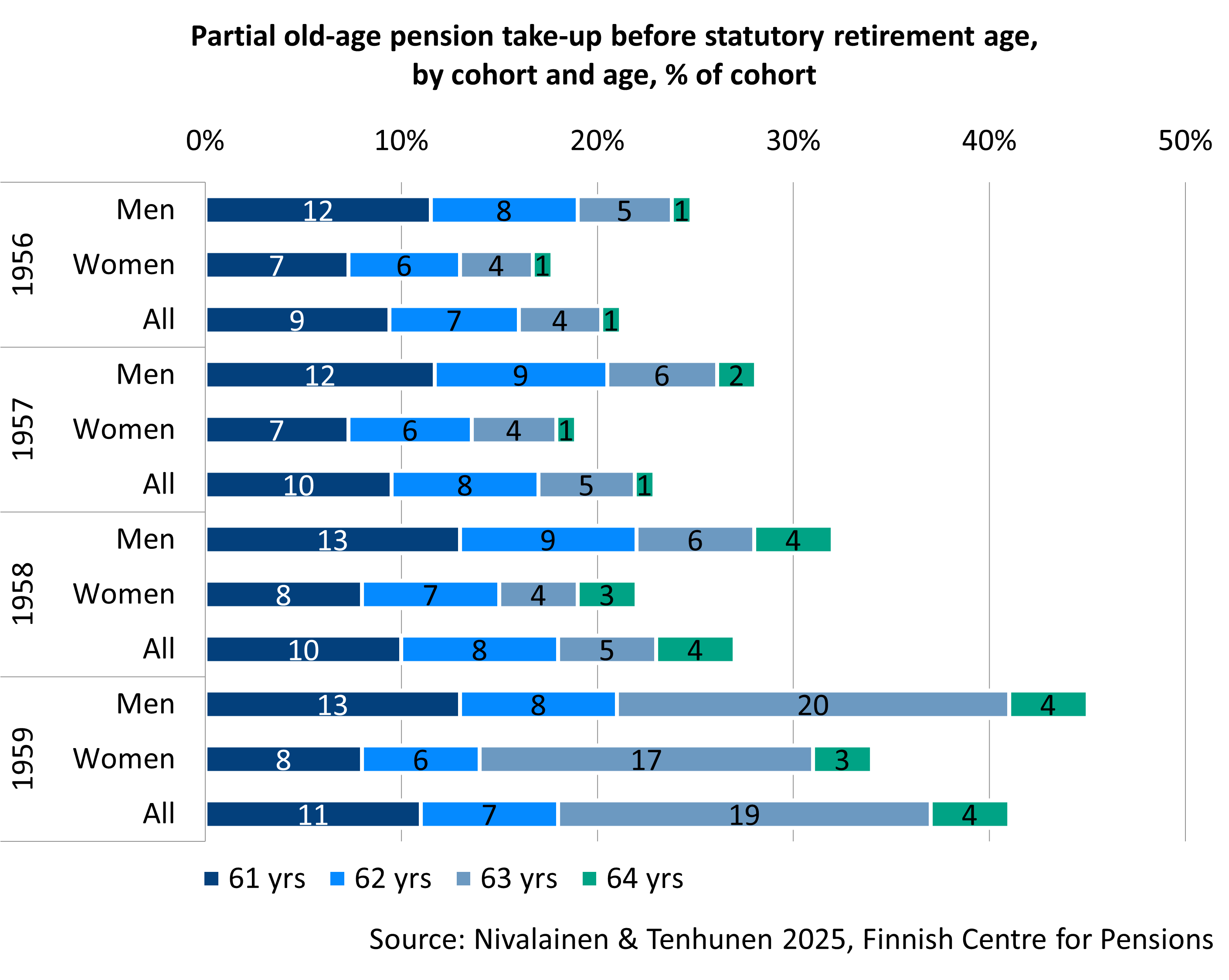

Most of those who have selected to take a partial old-age pension have taken it early, before reaching their retirement age for a full old-age pension – as a rule, as soon as they have turned 61. People draw the partial old-age pension for a longer period than before since the retirement age for the full old-age pension has risen but the lower age limit for the partial old-age pension has remained at 61 years.

Of those born in 1956, 20 per cent took the partial old-age pension before reaching their retirement age for the full old-age pension. Of those born in 1959, the equivalent figure is more than 30 per cent. Men select to draw the partial old-age pension clearly more often than women.

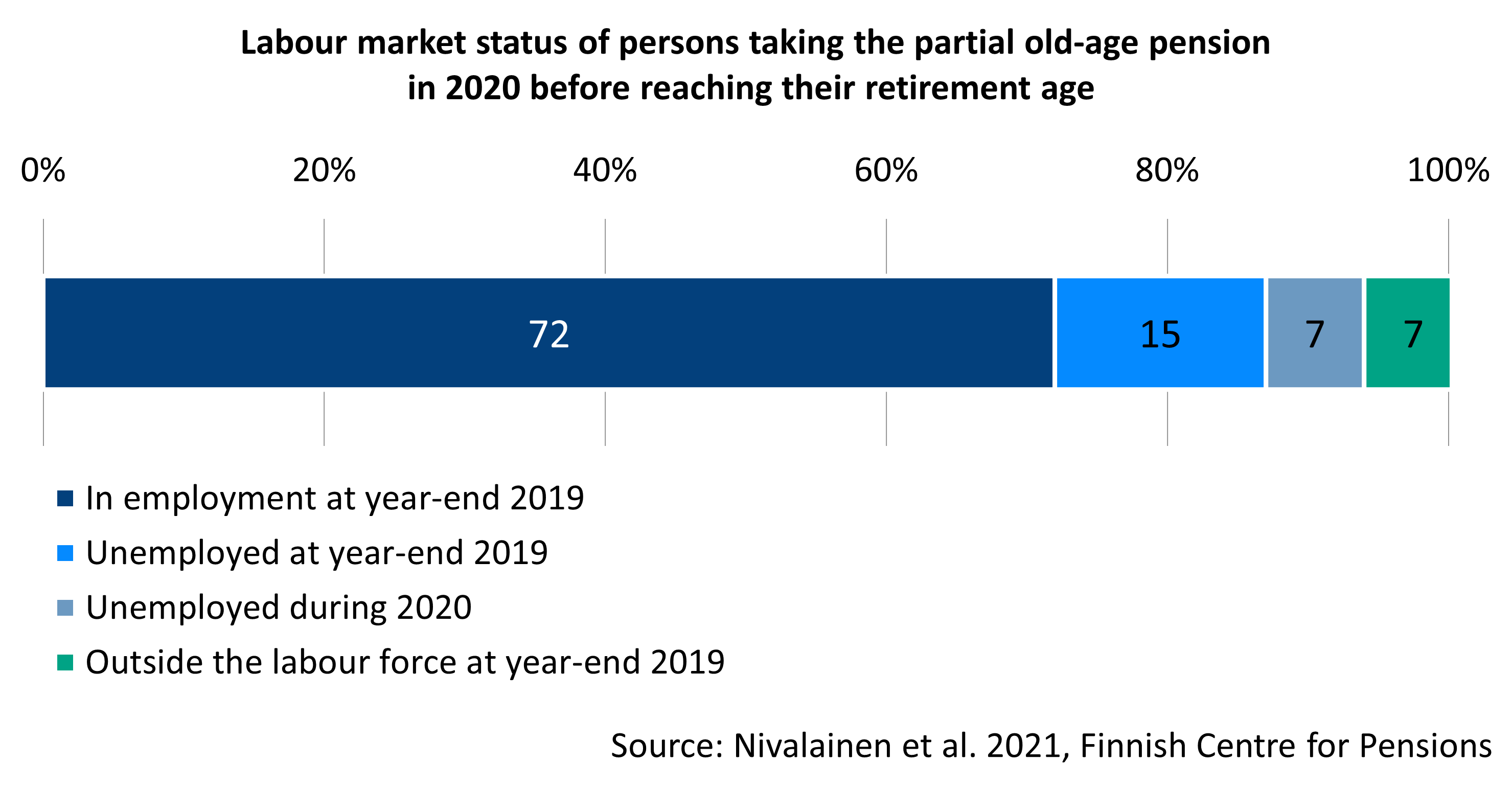

Employed people are by far the largest group of those starting to take a partial old-age pension. More than a fifth of those taking a partial old-age pension experienced unemployement around the take-up of a partial old-age pension.

Regardless of whether the person taking a partial old-age pension was working or unemployed when taking the pension, the labour market status tends to remain unchanged. Of those working, a majority continue working after taking the partial old-age pension.

Working usually not reduced after partial old-age pension take-up

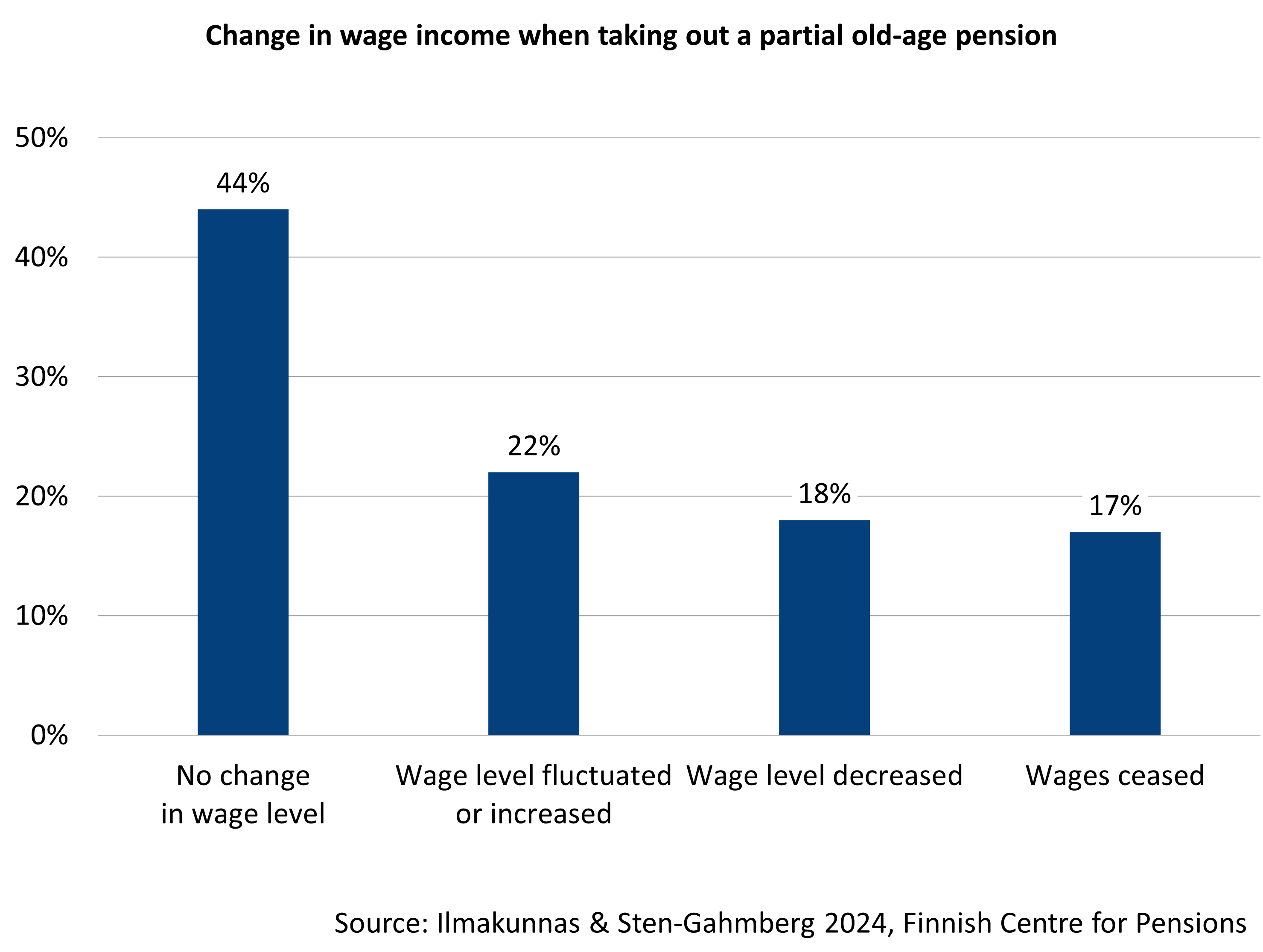

Many persons who draw the partial old-age pension continue working as before, without changes to their wage level. About one in five continue to work at a lower wage, that is, they seem to reduce their working hours. Almost one in five of those who worked before taking up the partial old-age pension stop receiving wages after the partial old-age pension begins. Nearly half of these people receive unemployment benefits.

Those who have chosen a partial old-age pension of 25 per cent will continue to work at a lower wage level more often than those who have taken a partial pension of 50 per cent. More generally than average, wage earnings end with those who have chosen a partial old-age pension of 50 per cent.

Especially in 2022, the number of persons taking up the partial old-age pension was clearly higher than before. The main reason for the rise in popularity was an exceptionally high index increase in earnings-related pensions. This resulted in a higher index increase for those who took out their partial old-age pension in 2022 compared to those who started their pension in 2023.

Certain groups take the partial old-age pension more often than others

Men, the self-employed, private sector workers, the unemployed and those with a longer working life are more likely than others to take the partial old-age pension before retiring on a full old-age pension.

Unlike its predecessor (the part-time pension), the partial old-age pension is not linked to working. The part-time pension required an employment relationship and a reduction in working hours. Among those working full time, the part-time pension and the partial old-age pension are each other’s opposites in terms of which population groups take the pension more often than others.

Women, public sector workers and the high-educated were more likely to take the part-time pension, while the partial old-age pension is more common among men, private sector workers and the low-educated.

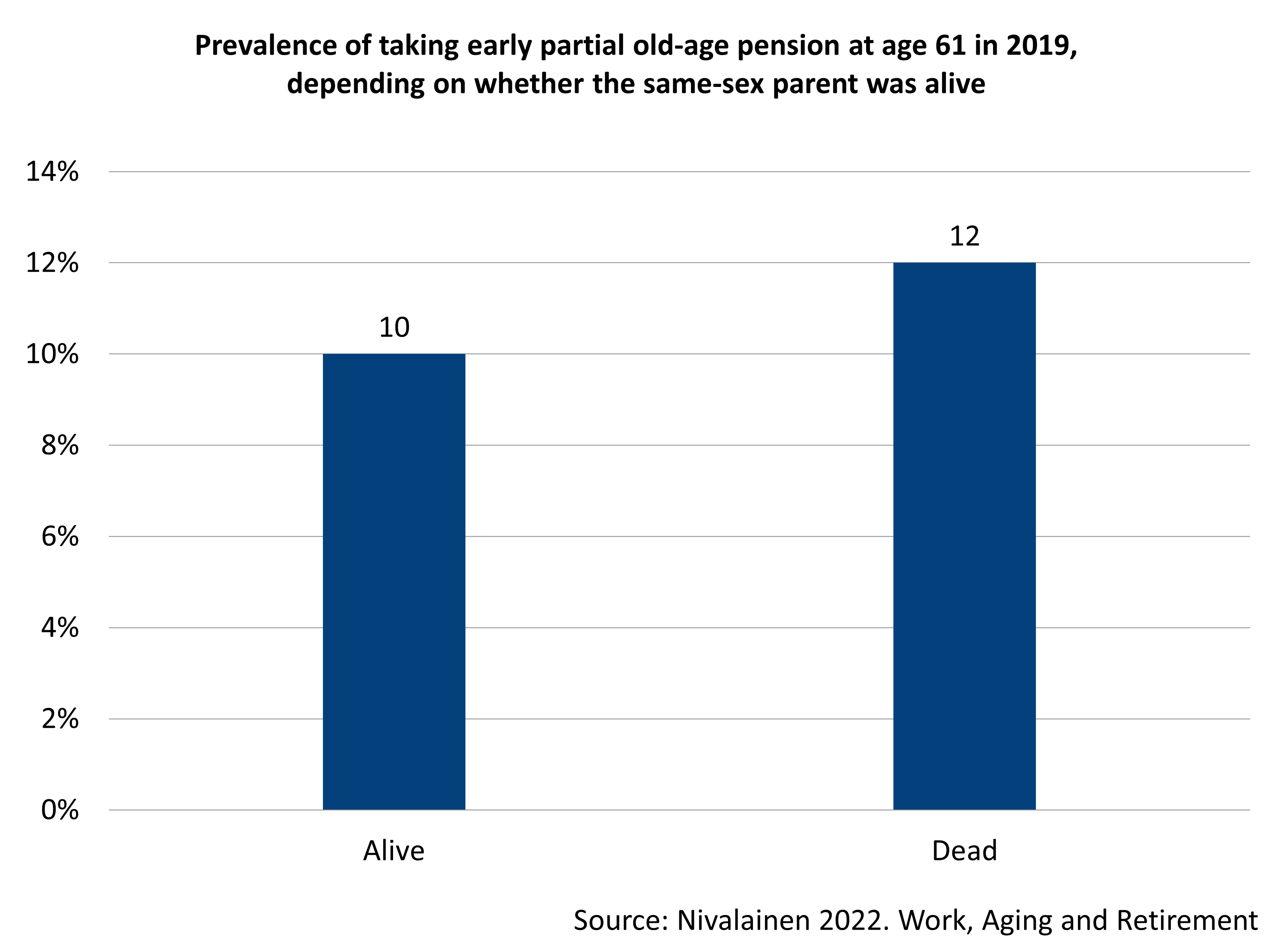

Persons with a shorter life expectancy benefit from taking the partial old-age pension at the earliest time possible. That way they receive more pension benefits during their lifetime than they would otherwise. In fact, it has been observed that persons whose same-sex parent had a shorter life more frequently take the partial old-age pension at age 61.

Taking the partial old-age pension after reaching the retirement age for the full old-age pension is rather rare. Less than one tenth of all new partial old-age pensions begin as deferred pensions.

Those with a higher education, longer working life or higher income more often than others take the partial old-age pension as a deferred pension. Self-employed persons, on the other hand, take the pension as a deferred pension less often than others.

Publications:

- Ilmakunnas et al. 2022. Osa-aikaeläke ja osittainen vanhuuseläke: Yleisyys, taustatekijät ja yhteys vanhuuseläkkeelle siirtymiseen [Part-time pension and partial old-age pension: prevalence, determinants and association with retirement] (Julkari)

- Ilmakunnas & Sten-Gahmberg 2024. Palkkatulot ennen ja jälkeen osittaisen varhennetun vanhuuseläkkeen ottamisen [Wage income before and after taking out a partial old-age pension] (Julkari)

- Kannisto 2023. Osittainen varhennettu vanhuuseläke ja työuraeläke. Uudet eläkelajit 2022 [Partial old-age pension and the years-of-service pension: new pension benefits in 2022]. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen et al. 2021. Partial old-age pension. A picture of claimants in 2017–2020. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen 2022. Early Pension Claiming and Expected Longevity: A Register-Based Study on the Take-up of the Partial Old-Age Pension in Finland. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen & Tenhunen 2025a. Osittaisen vanhuuseläkkeen varhennettuna ottaneiden ominaisuudet vuosina 2020-2023 [Characteristics of partial old-age pension claimants 2020-2023] (Julkari)

- Tenhunen et al. 2019. Who opt for a partial old-age pension? A study on the factors behinds the choice to take early payment of a partial old-age pension. (Julkari)

Those taking the partial old-age pension seem to retire early on the full old-age pension

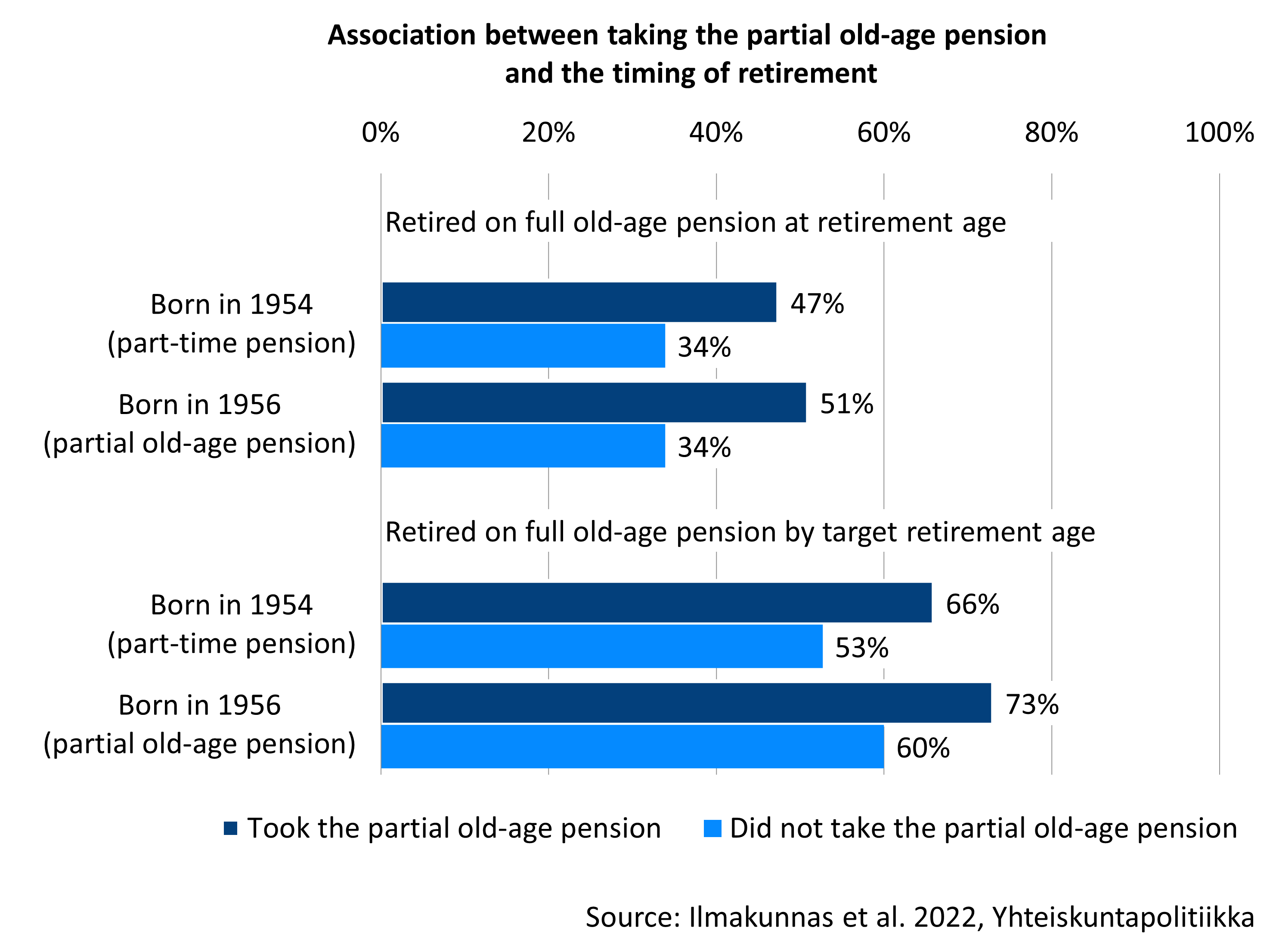

The hope is that the partial old-age pension will extend working lives and defer retirement. Of those born in 1956 who have taken the partial old-age pension, slightly more than half retired on a full old-age pension as soon as they reached their retirement age.

When we study the full-time employed, those who took the partial old-age pension at age 61 retired more often than others as soon as they reached their retirement age. They also continued working until their target retirement age less often than others. The same phenomenon was observed in connection with the former part-time pension.

According to statistics, about two-thirds of all partial old-age pensions taken before the retirement age have ended at the latest when the person has reached the their retirement age.

Publications:

- Ilmakunnas et al. 2022. Osa-aikaeläke ja osittainen vanhuuseläke: Yleisyys, taustatekijät ja yhteys vanhuuseläkkeelle siirtymiseen [Part-time pension and partial old-age pension: prevalence, determinants and association with retirement]. (Julkari)

- Nivalainen et al. 2021. Partial old-age pension. A picture of claimants in 2017–2020. (Julkari)

Pension reform 2005

The 2005 pension reform meant changes to the retirement age, early pensions and pension accrual. In addition, the pension-reducing life expectancy coefficient was introduced.

The aim of the reform was to raise the efficient retirement age and take the growth in life expectancy into account in pensions. Following the reform, more people worked until retirement age than before, the average retirement age rose and the minimum age for the flexible retirement age became the general retirement age.

Flexible retirement age and routes to early retirement

- The retirement age of 65 became a flexible retirement age between ages 63 and 68.

- The retirement age for the early old-age pension rose from 60 to 62 years. (This pension benefit was abolished in 2013.) The annual deduction for early retirement grew from 4.8 to 7.2 per cent.

- The reform also closed some routes to early retirement, of which the most important one was the abolishment of the unemployment pension as of the year 2012.

Pension accrual for the entire working life

- As of 2005, the accrued pension amount was calculated based on the earnings for each year of accrual instead of on the earnings for the last 10 years of employment.

- Pension began to accrue as of age 18 instead of at age 23, as it did previously.

- People were encouraged to work past the age of 63 with a higher earnings-related accrual rate (the accelerated accrual rate), which meant that pension accrued at an annual rate of 4.5 per cent of the annual earnings.

Life expectancy coefficient

- The life expectancy coefficient is a mechanism that adjusts the pension automatically to changes in life expectancy. As life expectancy increases, the life expectancy coefficient reduces the monthly pension so that the amount of pension received through the time spent in retirement remains, on average, on the same level.

- The life expectancy coefficient came into effect in 2010 and applies to persons born in 1948 or later.

Key pension rules before 2005 and in 2005–2016

| Pension rule | Before 2005 | 2005–2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Retirement age (old-age pension) | General retirement age of 65 years | Flexible retirement age 63–68 years. Insurance obligation ends at age 68. |

| Pension accrual rates at different ages | 23–59-year-olds: 1.5% of the earnings from the last 10 years of work 60–65-year-olds: 2.5% of the earnings from the last 10 years of work |

18–52-year-olds: 1.5% of annual earnings 53–62-year-olds: 1.9% of annual earnings 63–68-year-olds: 4.5% of annual earnings |

| Pension accrual after reaching the retirement age | Increment for deferred retirement 7.2% per year after age 65. | Accelerated accrual rate of 4.5% of the annual earnings at age 63–68 years. Increment for deferred retirement 4.8% per year after age 68. |

| Early old-age pension | Age limit 60–64 years | Age limit 62 years. Abolished in 2013. |

| Reduction for early retirement | 4.8% per year before age 65. | 7.2% per year before age 63. |

| Pension-reducing life expectancy coefficient | No | Yes |

Read more on Etk.fi:

Key results

- An increasing number of persons worked until the old-age retirement age because of the 2005 pension reform.

- Particularly the low-educated worked until the retirement age more often than before. The main underlying factor was that pre-retirement unemployment of the low-educated was cut in half.

- For the high-educated, the situation remained largely unchanged.

- The working lives of those who had retired on an old-age pension were clearly extended, particularly those of the low-educated.

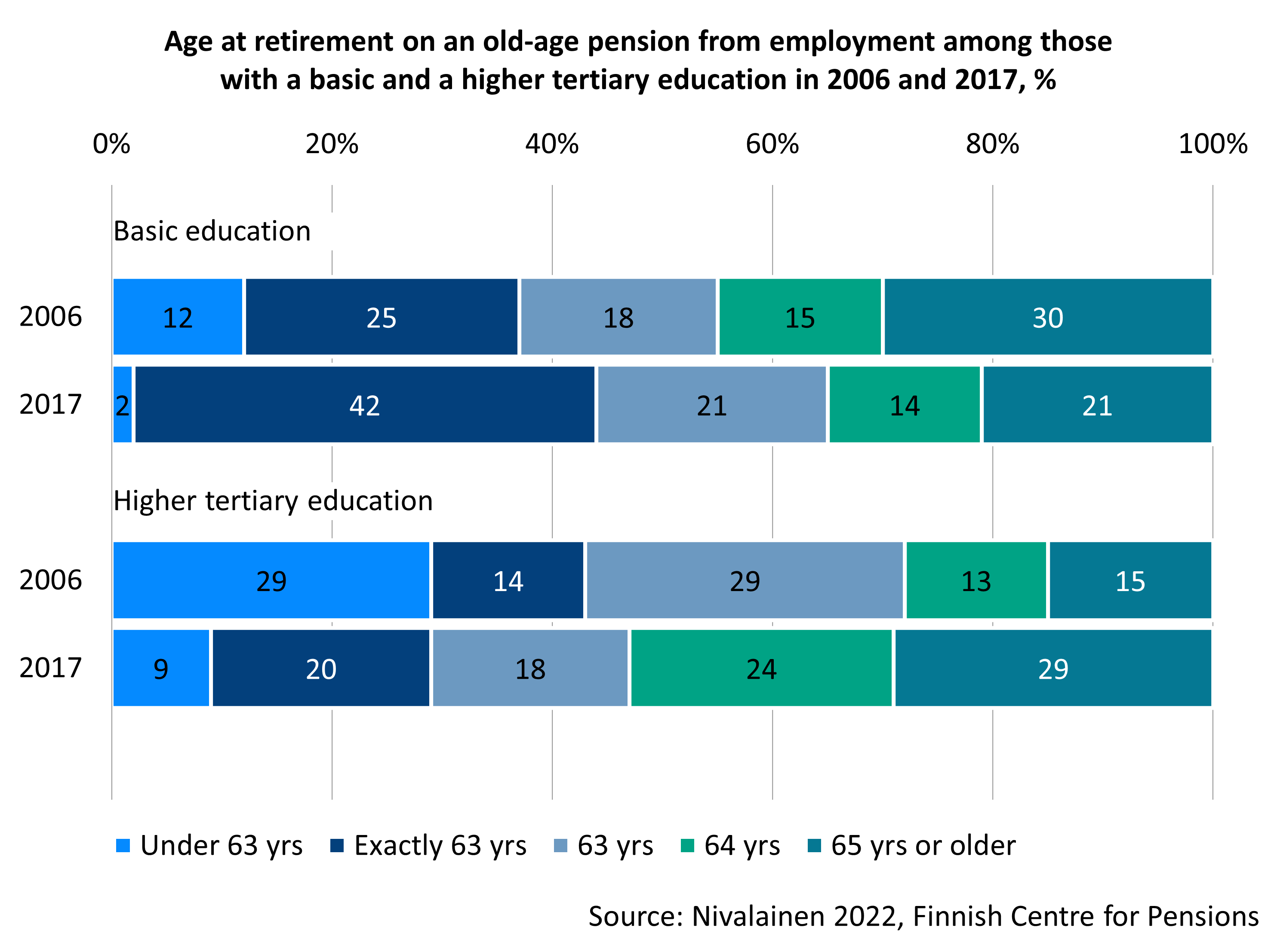

Clear educational differences when it comes to continued working

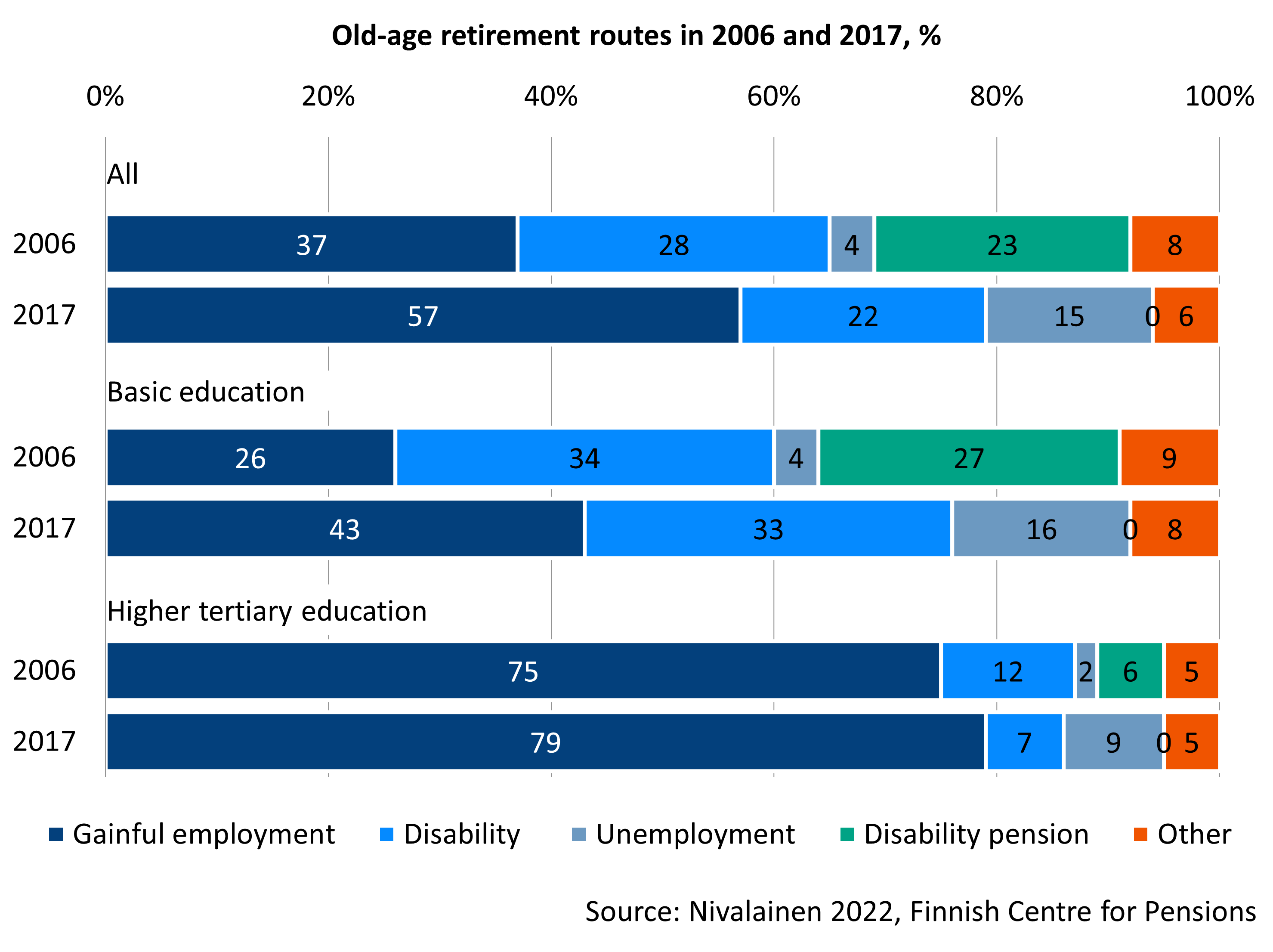

The share of persons retiring on an old-age pension from work grew because of the 2005 pension reform. In 2017, nearly 60 per cent retired on an old-age pension from employment. In 2006, the equivalent proportion was slightly under 40 per cent. There are no major gender gaps in the routes to retirement.

When examined by educational level, the differences between routes to retirement are considerable. The high-educated retire on an old-age pension from employment clearly more often than the low-educated. Among the high-educated, working until retirement age did not really increase after the 2005 pension reform. The low-educated continued working until old-age retirement more often than before and, at the same time, pre-retirement unemployment was reduced by half.

The unemployment pension was abolished in connection with the 2005 pension reform and the lower age limit for the unemployment pathway to retirement was raised. As a result, fewer than before retired on an old-age pension from unemployment.

Working lives extended for all, education-specific gap narrowed

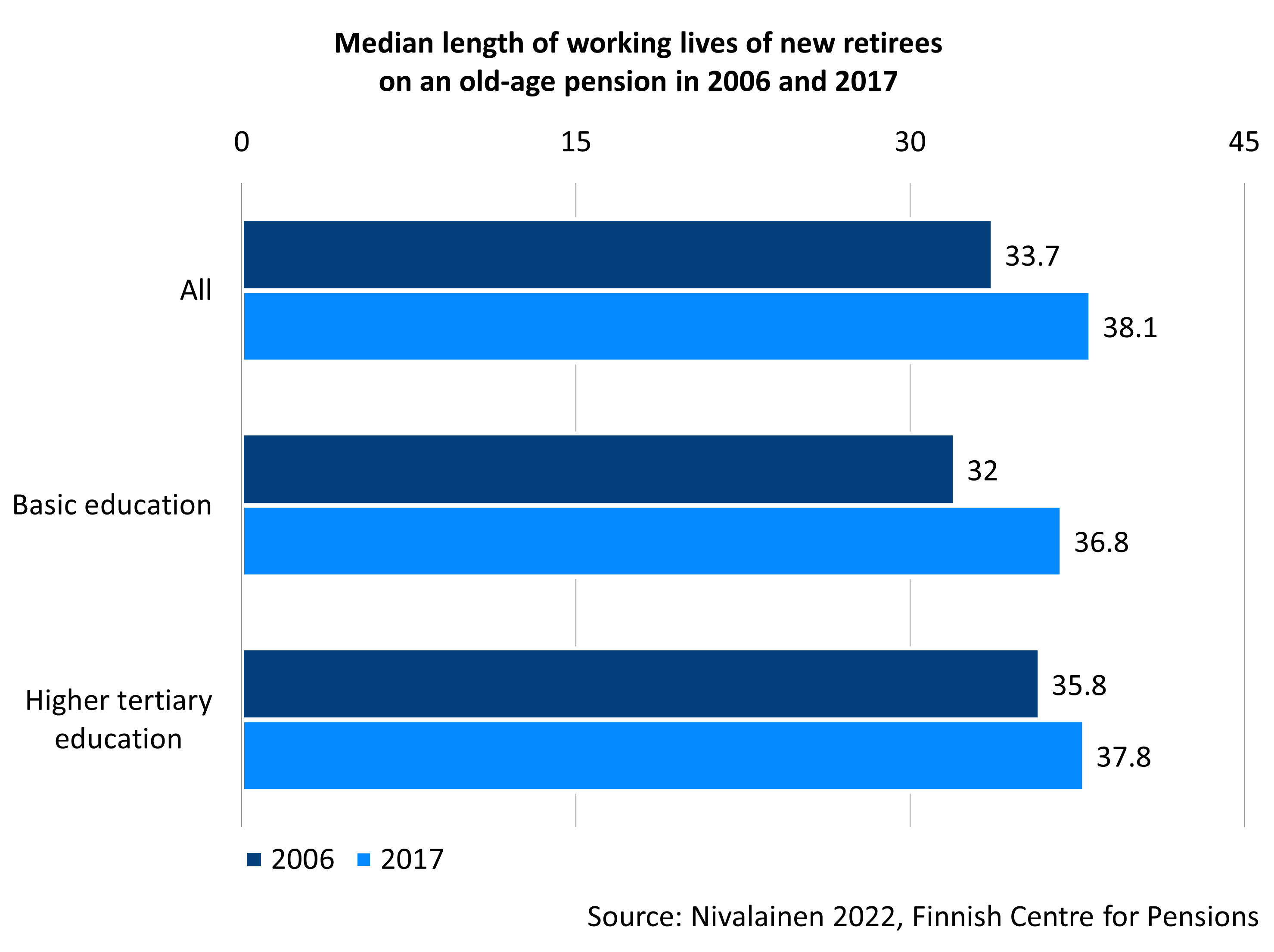

When an increasing number of people worked until reaching the retirement age, the average working lives also extended. The median length of all new retirees on an old-age pension increased from 33.7 years to 38.1 years after the 2005 pension reform.

Working lives extended the most for those with a basic education, from 32 years to nearly 37 years, and the least for those with a high education, from just under 36 years to just under 38 years.

Read more on Etk.fi:

Publications:

Key results

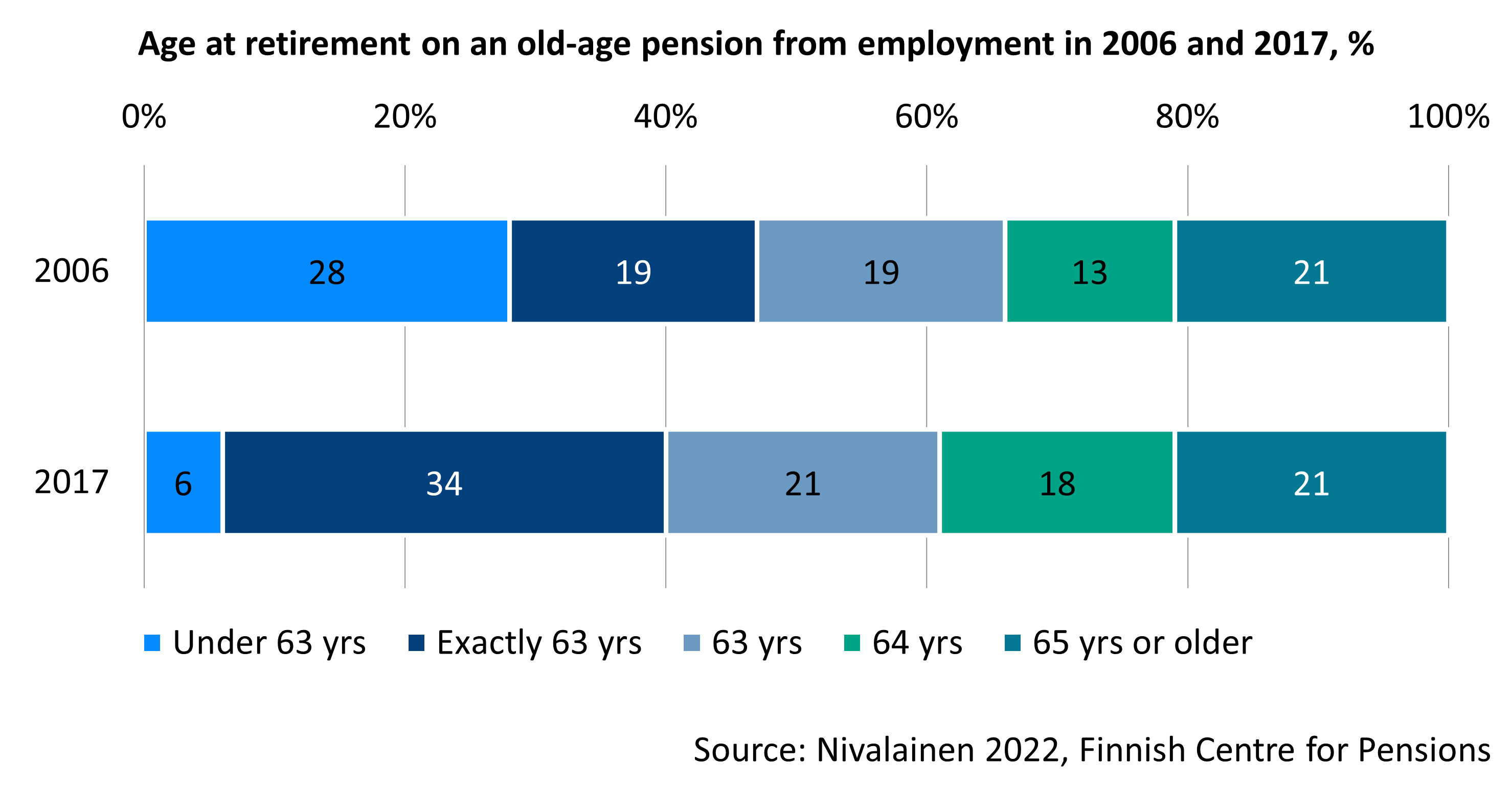

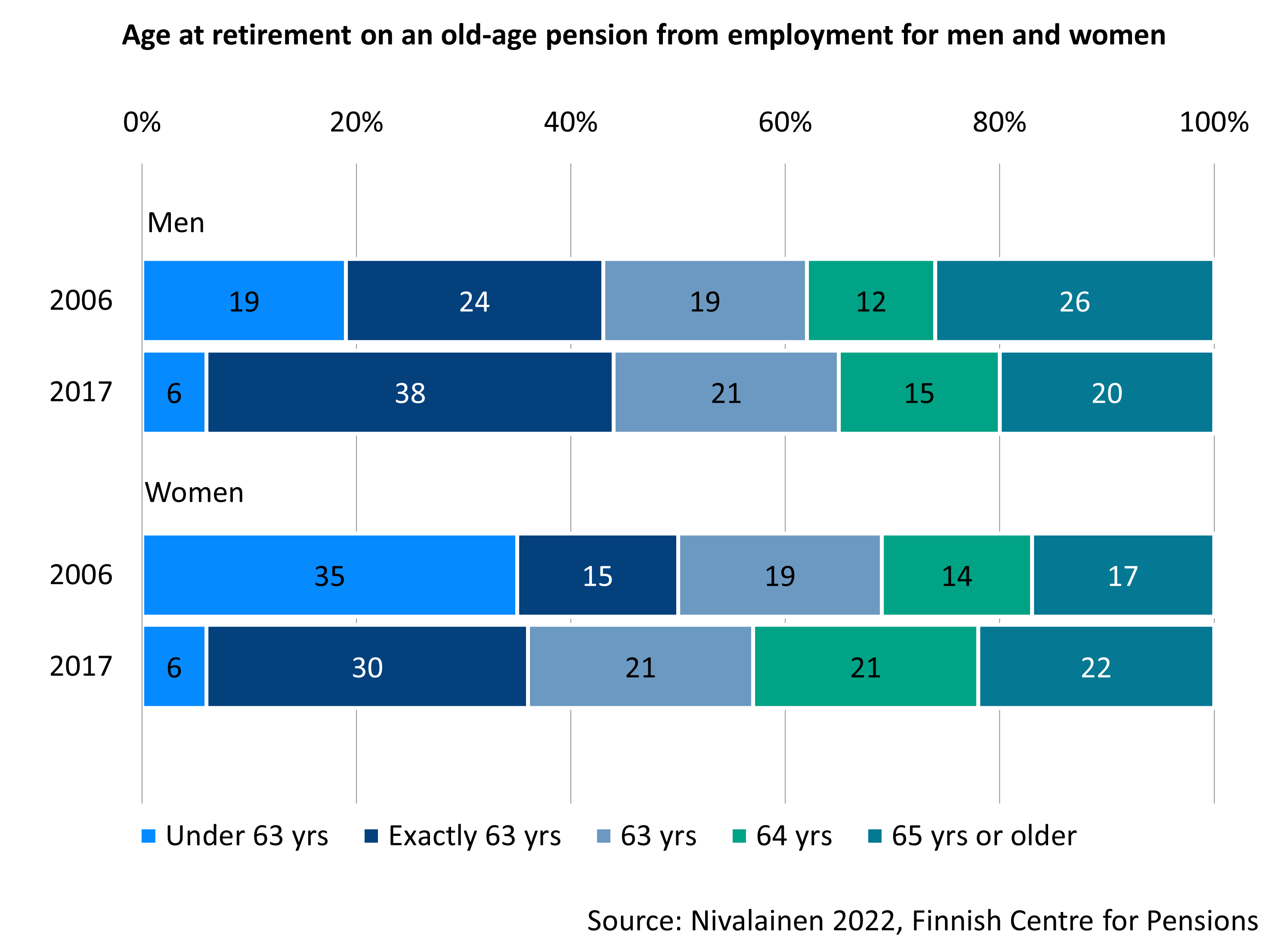

- After the 2005 pension reform, the focus for transfer from work to old-age pension shifted from under 63 to 63 years of age. At the same time, the average effective retirement age rose.

- The share of persons working until age 65 or older remained unchanged.

- Extending working lives became less common in the private sector and more frequent in the public sector.

- Extending working lives increased among women and the high-educated.

Age at transfer from work to old-age pension rose

After the 2005 pension reform, the focus for transfer from work to old-age pension changed. In 2006, most people retired at an age under 63 years, while in 2017, the most frequent age at retirement was exactly 63 years. In the same period, the share of persons who retired on an old-age pension at age under 63 decreased clearly.

The share of persons who retired at age 65 or older remained unchanged after the 2005 pension reform. Both in 2006 and 2017, one fifth of the new retirees on an old-age pension retired at age 65 or older.

As a result of the above-described development, the average age at retirement from work rose from 62.9 years (in 2006) to 63.8 years (in 2017).

Publications:

Transition to old-age pension developed differently in the private and the public sector

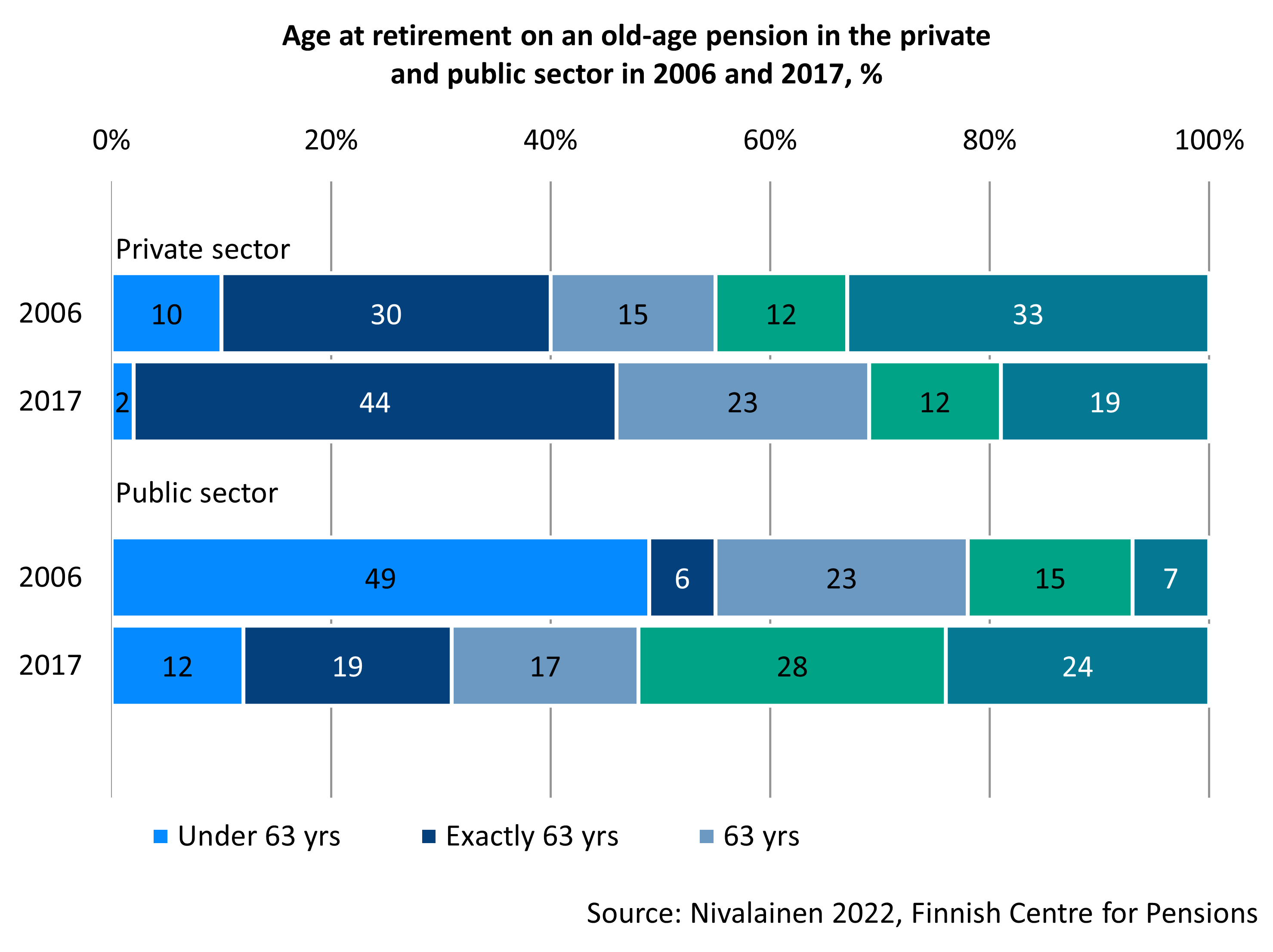

After the 2005 pension reform, markedly extending working life became less common in the private sector and more frequent in the public sector

In the private sector, the most common age of retirement from work on an old-age pension was 65 years in 2006. One third retired then at the earliest. In 2017, the most common age of retirement was exactly 63 years. More than two in five retired on an old-age pension immediate when they turned 63, and only one in five continued working until at least age 65.

In the public sector, the development moved in the opposite direction. The most common age for retirement was under 63 years in 2006. One in two retired before age 63 and less than one in ten at age 65 or older. Underlying this development was largely the extensive role of occupational retirement ages of less than 63 years in the public sector.

In 2017, the most common retirement age in the public sector was 64 years, with half continuing to work until at least that age. One quarter retired at age 65 at the earliest. This was partly because a large share of public sector employees has an individual retirement age that is higher than 63 years and the significance of occupational retirement ages has decreased.

In the private sector, the average retirement age has not risen since the 2005 pension reform, but in the public sector, it rose clearly.

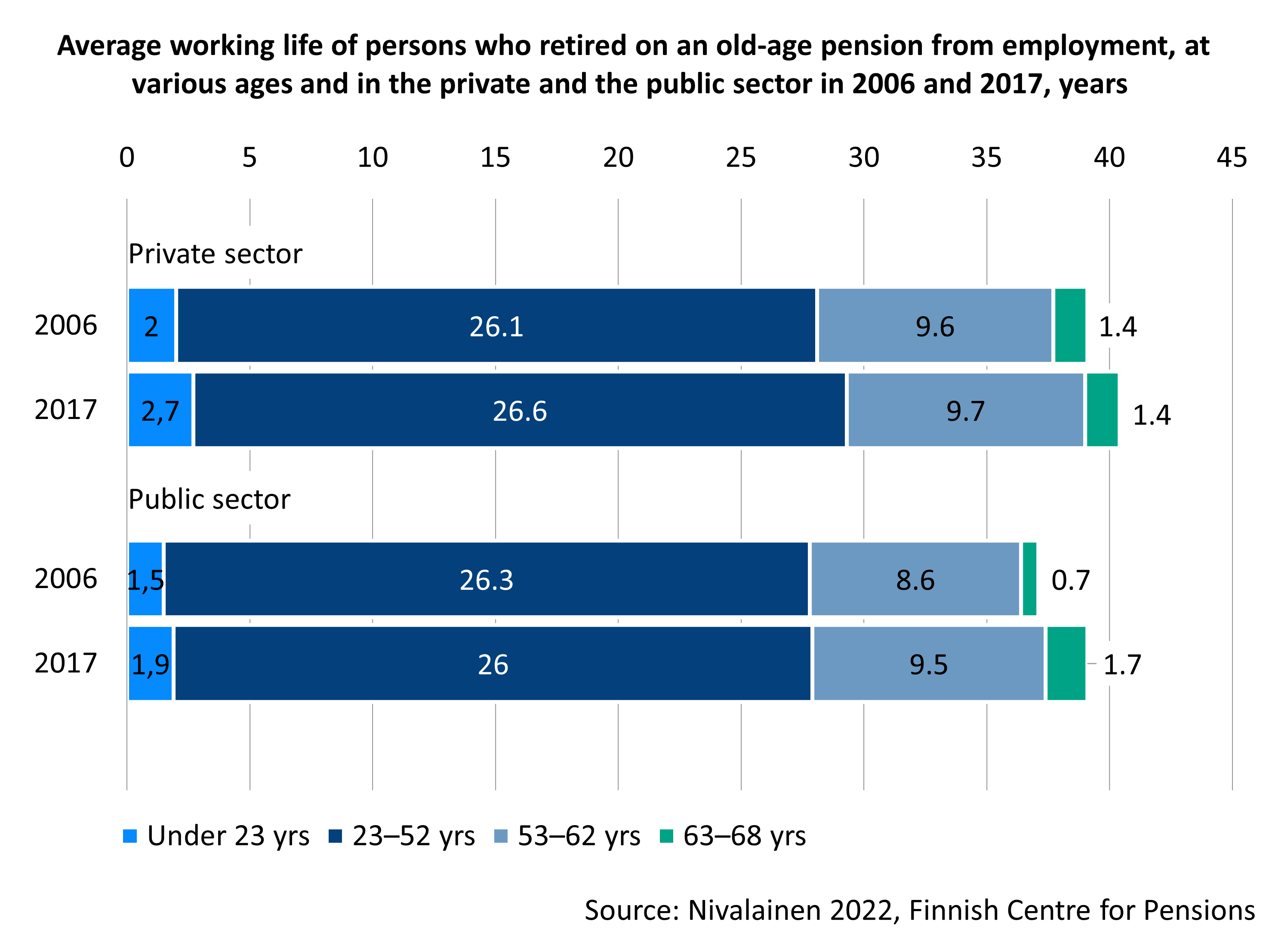

In the private sector, working life between ages 63–68 did not grow after the 2005 pension reform, but in the public sector, working lives between these ages extended by one year. In the public sector, working life expanded also between the ages of 53–62 years.

Extending working lives at higher ages reflects that, in the public sector, early retirement (before the age of 63) has largely been replaced by continued working until age 64 or older.

Publications:

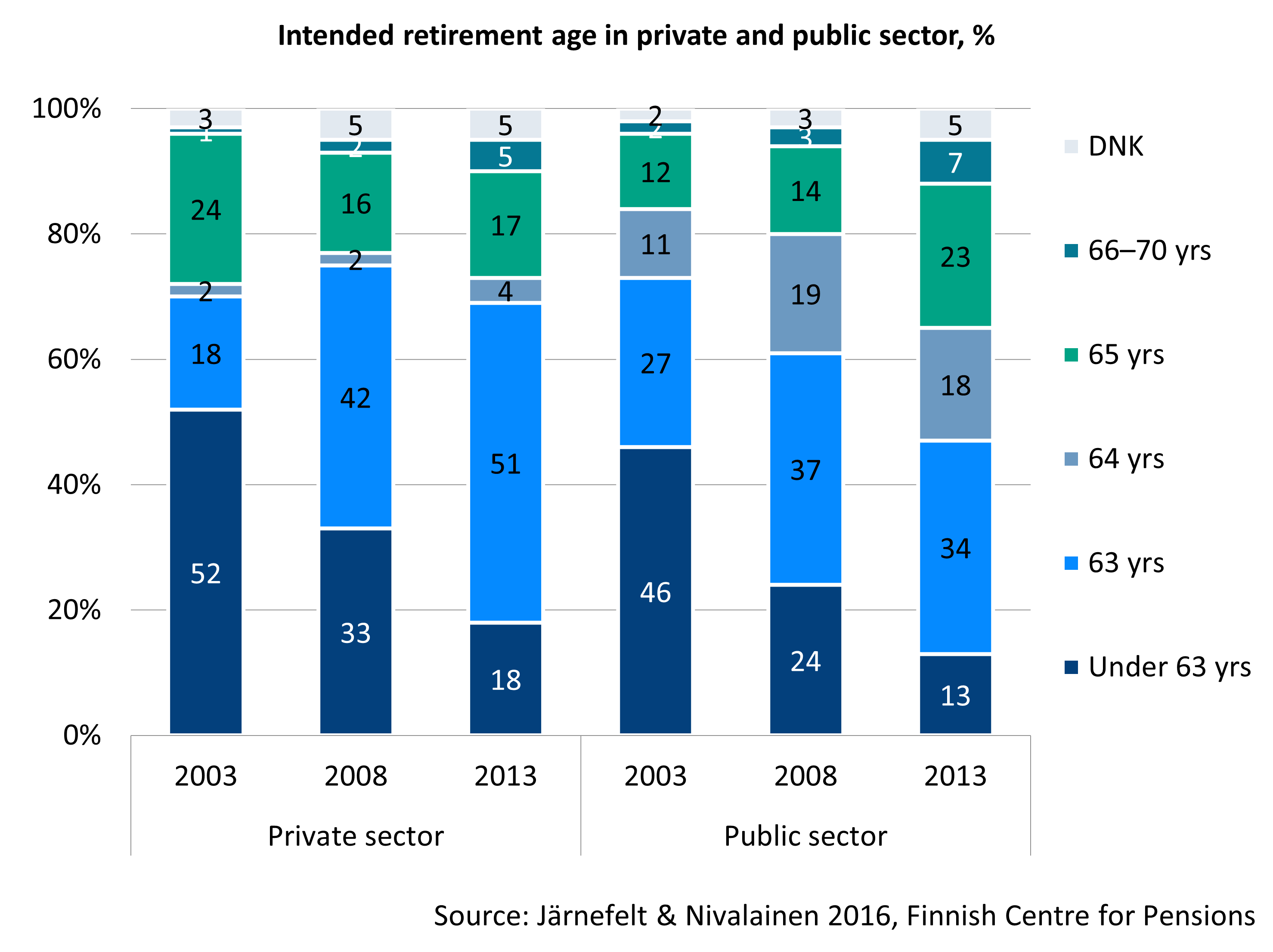

Different development between private and public sector reflected also in retirement intentions

The intended retirement age of private and public sector wage earners aged 50 or older developed differently after the 2005 pension reform. In 2003, private sector employees intended to retire after age 63 slightly more often than public sector employees.

After the reform, the share of public sector employees who intended to retire after age 63 grew clearly by 2008 and even more by 2013. In the private sector, this share did not increase much in either year. In 2013, clearly more public sector employees than private sector employees assessed that they would retire after age 63.

Publications:

Women and highly educated continued working longer than before

After the 2005 pension reform, working longer increased among women and declined somewhat among men. In 2006, men retired later than women, but by 2017, the situation was the reverse.

The gender gaps in the transition to retirement reflect, in part, sector differences. The development in transition to retirement in the public sector is reflected in the age at retirement of women since more than half of the women approaching the retirement age work in the public sector. Most men, on the other hand, work in the private sector.

Extended working lives increased among the high-educated and decreased among the low-educated after the 2005 pension reform. In 2017, the high-educated continued working longer more often than the low-educated. In 2006, the situation was still the reverse.

After the 2005 pension reform, the pension accrual rate (the so-called accelerated accrual rate) linked to earnings was higher for work done after reaching the retirement age. Since the high-educated and those with a high working life status more often continued working after they had turned 63 years than did the low-educated, the accelerated accrual rate favoured particularly the high-educated and those who were well off. This may have increased socio-economic differences in pension levels.

Pension accrual as of age 18 agreed on in the 2005 pension reform was a significant change in principle. The change was successful from the point of view that it benefits particularly those with a lower socioeconomic status. For example, blue-collar workers who retired from work on an old-age pension in 2017 had been in working life for more than three years before age 23 while upper white-collar workers had only been working for about one year at that age.

Publications:

Key results

- Thanks to the flexible retirement age, the 63- and 64-year-olds could retire on a full pension while, before the 2005 pension reform, retiring at that age reduced the pension permanently via the reduction for early retirement.

- The accelerated accrual rate was not high enough to offset the effect of the abolished reduction for early retirement. That way, the incentives to continue working weakened.

- The reform increased retirement at age 63 and 64.

- According to a survey, the accelerated accrual rate impacted the decision to continue working past the age of 63 for some.

The 2005 pension reform aimed at deferring retirement using financial incentives. For work done after the age of 63, pension accrued at a rate of 4.5 per cent of the annual earnings. This was thought to encourage people to continue working past the age of 63.

The financial incentives to retire increased because the retirement age changed

After the 2005 pension reform, the 63- and 64-year-olds could retire on a full pension while, before the reform, retirement at that age reduced the pension via the reduction for early retirement. That is why, following the reform, the pension wealth at age 63 and 64 increased by 9.6 and 4.8 per cent.

The accelerated accrual rate was not high enough at age 63 and 64 to offset the effect of the abolished reduction for early retirement. As a result, an additional year of working benefited people of this age less after the reform. As a result of the flexible retirement age, the incentives to continue working for 63- and 64-year-olds weakened while the incentives to retire grew.

The changes in incentives were reflected in retirement: retirement at age 63 or 64 increased clearly after the reform. Relabelling the pension type from early retirement to full retirement alone increased retirement.

As a result of the 2005 reform, the peak in retirement in the private sector changed from age 65 in 2004 towards age 63 in 2005. Long term, age 63 became the ‘new normal’ retirement age instead of age 65.

This development does not mean that the financial incentives would not have worked as they intended. A greater additional benefit from continuing working reduces retirement. However, after the 2005 pension reform, continued working benefitted the 63- and 64-year-olds less than before, so the financial incentive was negative. That is why retirement increased.

Publications:

- Gruber et al. 2019. The Effect of Relabeling and Incentives on Retirement: Evidence from the Finnish Pension Reform in 2005 (labore.fi)

- Leinonen et al. 2016 Health as a predictor of early retirement before and after introduction of a flexible statutory pension age in Finland (Social Science & Medicine)

- Nivalainen et al. 2020. Carrots, sticks and old-age retirement: A review of the literature on the effects of the 2,005 and 2,017 pension reforms in Finland (Nordisk Välfärdsforskning | Nordic Welfare Research)

- Ollonqvist et al. 2021. Incentives, Health, and Retirement: Evidence from a Finnish Pension Reform (VATT Working Papers)

- Uusitalo & Nivalainen 2013. Vuoden 2005 eläkeuudistuksen vaikutus eläkkeellesiirtymisikään [2005 pension reform’s effect on age at retirement] (Julkaisuarkisto Valto)

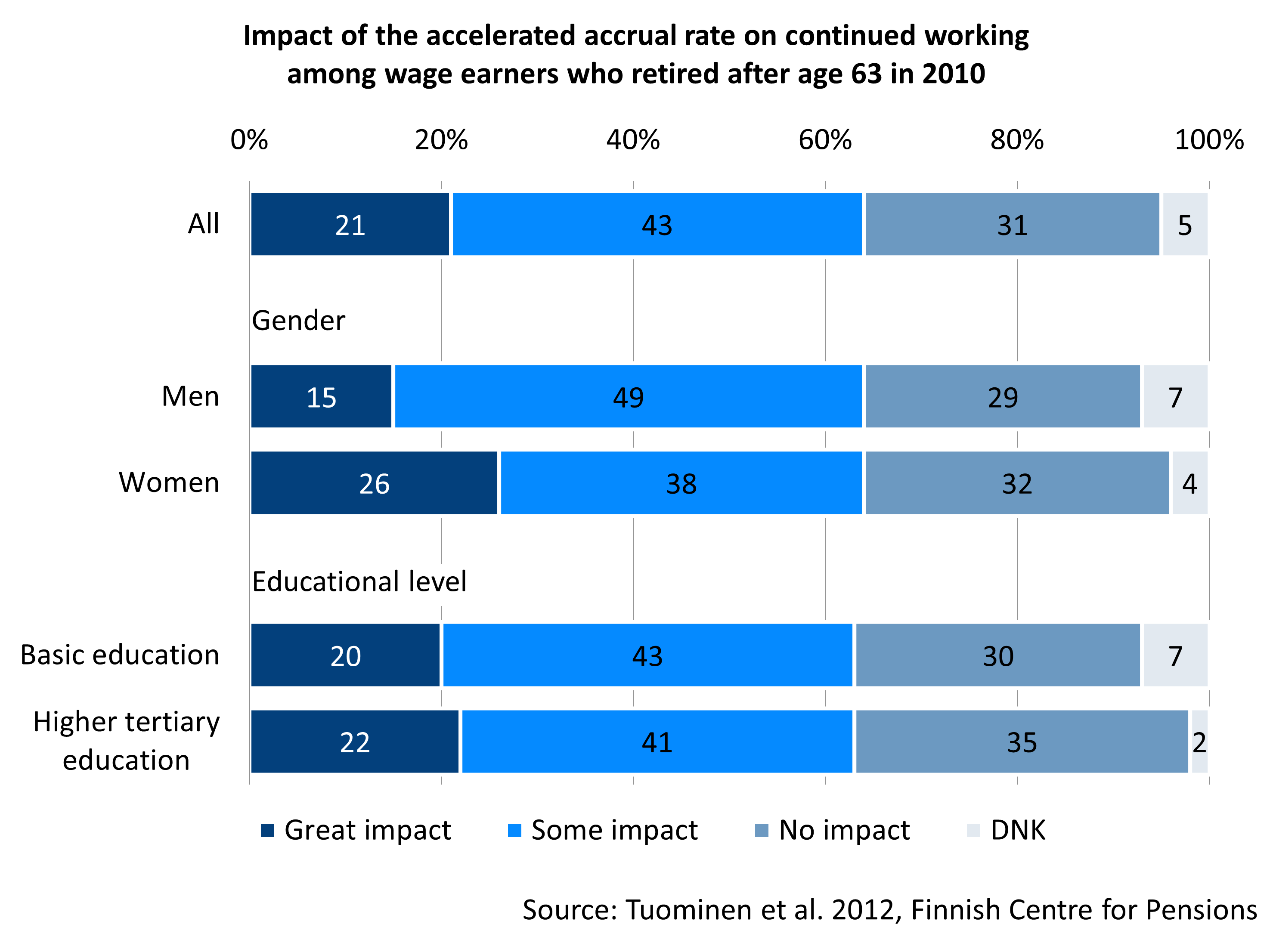

The accelerated accrual rate encouraged some to continue working

In a survey done among wage earners who retired on an old-age pension in 2010, the accelerated accrual rate had impacted the decision to continue working past age 63 for some. It had had a great impact for continued working for every fifth person who had continued working after reaching the retirement age. For nearly half of the persons who belonged to this group, the accelerated accrual rate had had some impact.

A higher pension was an almost equally high motivator for both genders, but women replied more frequently than men that it played a very significant role. There were no gaps in terms of educational level, but the longer retirement was deferred, the greater the assessed impact of a higher pension.

Publications: