Divided Europe in terms of pensioners’ economic welfare

Pensioners in Europe have considerably more money to spend today than in the early 2000s. The poverty rate has gone down by around 20%, and the gap in income between pensioners and working-age people has become narrower. These are all good news about pensioners’ economic welfare in Europe. But if we look at this from a more differentiated angle, we see that there is more to the story.

EU pursues multidimensional poverty indicators

Reducing poverty and preventing social exclusion is one of the spelled-out goals of the Europe 2020 strategy. The multidimensional goals set in the strategy mean that poverty is measured more widely. Instead of just looking at income levels or at-risk-of-poverty (AROP) rates, which define poverty as having an income that lies below 60% of the national median, the Europe 2020 indicators also include income inequality and a subjective perception of poverty. These indicators provide a meaningful framework for assessing the economic wellbeing of Europe’s pensioners from a wider perspective and were also used in our recent study.

Low average income is not the same as high risk of poverty

The purchasing power of pensioners’ annual income varies greatly in Europe. The median income in top-ranking Luxembourg is about seven times as high as that in Romania. Even the EU average is three times higher. It comes as no surprise that the purchasing power is still the weakest in the new member states of Eastern Europe and some Southern European countries.

However, the average level of pensioners’ income does not go hand in hand with the AROP rate. Pensioners’ AROP rate is also sensitive to changes in the working-age population’s income situation, which has deteriorated during the financial crisis. Also, an unequal distribution of income both among pensioners and the working-age population relates to a higher poverty rate. Slovakia and the Czech Republic are examples of countries with a below-average income but an equal income distribution and low AROP rates at the same time.

Subjective perceptions of poverty divide Europe

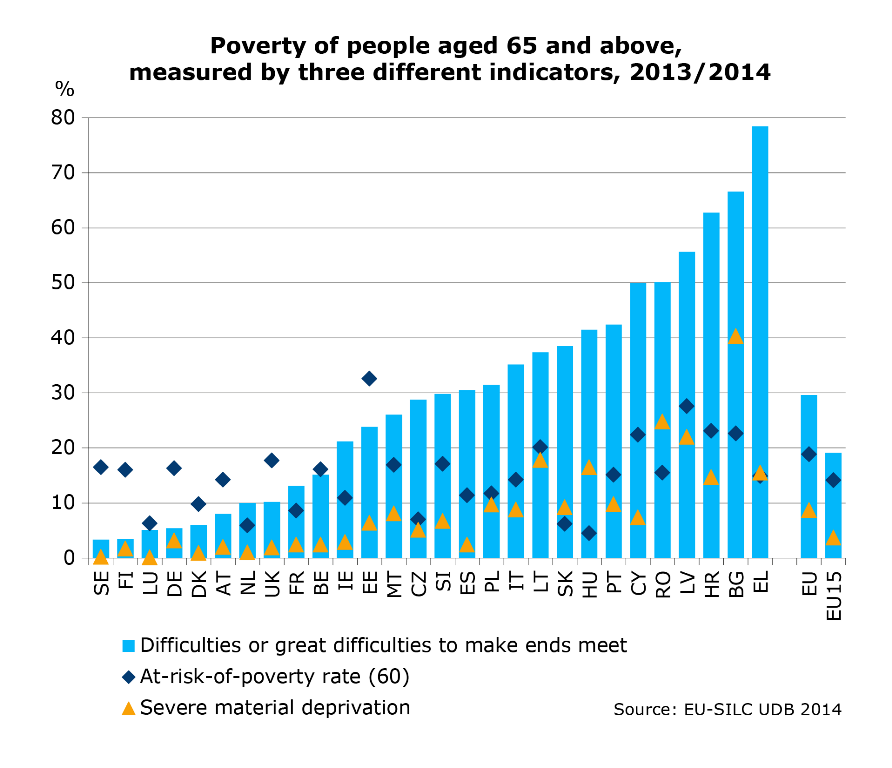

Once we shift the perspective to how pensioners see their own economic situation, the picture gets less optimistic and even more divided. The figure below displays the share of people over 65 years in each EU member state in 2013/2014 who (a) report difficulties or great difficulties in making ends meet, (b) suffer from severe material deprivation, or (c) face the risk of poverty.

A great deal of pensioners in Central and Eastern European new member states, but also in Southern Europe, find it difficult to cover their material needs and making ends meet. In contrast, material and self-perceived poverty among the elderly is very rare in Northern and Western Europe. The inconsistency of different poverty measures is particularly obvious in Sweden and Finland, on the one hand, and in Romania and Portugal, on the other. The AROP rate of all these countries is close to the EU average, but the levels of perceived material poverty differ greatly. The level of income and its purchasing power may not tell the whole story, but in contrast to AROP rates, it corresponds to a high degree with the pensioners’ own experiences of poverty.

In part, the huge difference in the perceived and the material poverty of Europe’s elderly may result from cultural and societal differences. In some countries, people may be more reluctant to admit economic strain than in others. The elderly may also see their economic position and needs in relation to the youth and the working-age population in a different way. At any rate, looking at pensioners’ economic welfare from different angles still reveals a highly divided Europe. It leaves us with a whole lot more to do in order to reach the goals set out in the Europe 2020 strategy as far as old-age poverty is concerned.